What do gambling shows talk about?

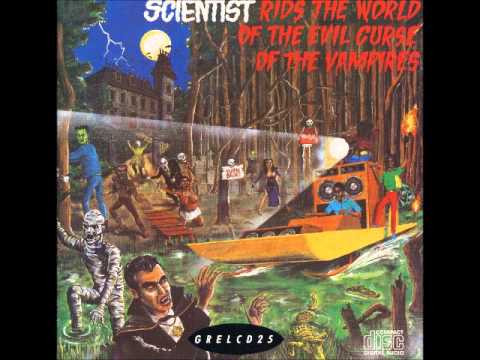

Song: Scientist, "Plague of Zombies"

This is a departure from the usual content on here, in that there's no real math or analysis. There's also not much of an audience for this website yet, so I hope you'll indulge me this week.

I was curious what all these gambling shows talk about for hours, when the picks they produce collectively appear to be no better than randomly chosen. I'm always interested in how people make decisions. How does their process work for choosing what bets to take? How might it work better?

Before I get too far into this, I know I'm being a killjoy. These podcasts are for entertainment purposes, just like betting is entertainment for a lot of people, not a sincere attempt to make money over the long term. Some degenerate gambling behavior is part of the appeal of these podcasts. They're selling the idea that "gambling is fun" as much as any particular bets.

It's still weird to be a gambling expert who can't do better than a coin flip.

I previously showed how combining multiple machine learning algorithms thru voting will only improve results when they make independent mistakes, and are significantly better than guessing. Those are both pretty intuitive conditions, and I think they're true of groups of people as well. If everybody has the same opinion, or makes the same sort of mistakes, or nobody really knows anything, there can't be a wisdom of crowds.

Humans have a big advantage over combining machine learning algorithms. We can talk with each other, challenge each others' assumptions, provide counterexamples, and so on.

There's not a ton of that in the gambling podcasts I listened to. Gambling talk is all about inventing stories about the future. It's sort of a competition for who can pitch the best narrative for the game. These stories are almost their own literary genre, and the construction of these are more important than the picks themselves. There aren't a lot of opportunities for the wisdom of crowds or some sort of error correction to occur.

Imagine I had a magic black box that was right about NBA lines 56% of the time. I could sell those picks, and be one of the better handicappers on the internet. While I could certainly write a little story for each one, maybe in the style of Raymond Carver -- "Will You Please Take The Over, Please?" -- the story doesn't make the bet more likely to be true, though, right? A factual story would be the same for every bet, and not very interesting: "there is slightly more value on this side of the bet, according to the model."

What we talk about when we talk about sports betting

Gambling personalities are always talking about what has happened in the past -- connections to previous games they've bet on, dubious historical trends, and the tendencies of certain players. Interactions like, "I thought you had a rule never to bet against Baker Mayfield?" "But he's 2-7 on the road in early Sunday games after a Monday night game where he got over 30 rushing yards."

These arbitrary connections remind me of a bit from Calvino's Invisible Cities:

In Ersilia, to establish the relationships that sustain the city's life, the inhabitants stretch strings from the corners of the houses, white or black or gray or black-and-white according to whether they mark a relationship of blood, of trade, authority, agency. When the strings become so numerous that you can no longer pass among them, the inhabitants leave: the houses are dismantled; only the strings and their supports remain.

There were quite a few of those useless strings in the November 6th episode of the Ringer Gambling Show.

The top bun

On a couple of occasions, the show discussed whether certain information was already priced into the line or not. Since gambling should be about determining which bets have positive expected value, that's a very useful thing to discuss. "If this spread looks wrong, what does the market know that we don't? Or what do we know that the market doesn't?"

If the goal is to win, the implicit question should always be: why do we think we have an advantage over other gamblers taking the other side? Why are we special? Why do we think the line isn't perfect?

Superstitions and biases

They were resistant to bet on teams that they had recently lost money on -- not wanting to get burned again. This is clearly not a financial choice, but an emotional one. The axe forgets, the tree remembers.

Team loyalty also affected their betting decisions. They avoided taking Baltimore because Ariel is a Ravens fan (the bet would have won). Jon suggested betting against his team, the Dolphins, which Ariel jokingly called "an emotional hedge". The Dolphins won. So they cost themselves two potential wins due to their fandom.

They decided not to take a bet on Houston (which ended up winning) because, in Jon's words, "betting on Davis Mills is not a pleasant experience". Whether a team or player was fun to bet on came up a couple of other times as well. Someone just trying to make a profit wouldn't care how fun the games are to watch. They might not even watch the games at all. Whether the gambler watches the game or not has no influence on the outcome.

Bets need to be fun, not just a good value. These gambling experts still want to experience "the sweat" -- watching the game and rooting for their bet to win. As I wrote last week, betting on the Browns and losing is like losing twice, so even if the Browns are a better value, they are a bad pick for emotional reasons. Who wants to have to be a Browns fan, if only for a few hours?

It's sort of like Levi-Strauss said about food. It's not enough that a type of food is good to eat, it must also be good to think about. The Houston Texans led by Davis Mills are not "bon à penser".

Not enough useful disagreement

All three of the bets they were in total agreement on (PIT, TB, ARI) lost. Nobody presented a case against those bets, so there was no opportunity for any of them to change their minds or reconsider their beliefs.

I'm not endorsing pointless contrarianism -- not every side needs to be argued. Don't be that one guy in every intro to philosophy class. But if both sides of an issue (or a bet) have roughly equal chances of being true, there should be a compelling case to be made for either side. Someone who can't make both cases fairly convincingly probably doesn't know enough to say which case is stronger.

Two types of hot streaks

For gamblers, there's one type of hot streak that's always bound to end. A team has won a few games it shouldn't have won, therefore they're bound to lose the next one. Their lucky streak will fail. In the real world, there's no invisible hand that pulls things down to their averages on a set schedule. In a small sample size of 17 games in an NFL season, there's no reason to think things will be fair by the end, much less the very next game. Now, a team could be overvalued by the market because they got some lucky wins, which makes them a value to bet against. But teams don't have some fixed number of "lucky games" every year, and once they've burned through those, their luck has to turn.

The other type of hot streak is bound to keep going. The team were divided whether to bet the Rams or not. They decided to go with Ariel's opinion, because she's been on a hot streak lately. If Ariel's record was demonstrably better than the other two hosts' over a long period of time, it would make sense deferring to her as the tiebreaker. But winning a few bets in a row doesn't mean the next bet is any more likely (or less likely) to win. As a teammate, that's a supportive thing to do, so I'm sure that's part of it. But people who gamble tend to think they have it sometimes, and don't have it other times. Sometimes they're hot, sometimes they're cold.

We've seen this before with NBA basketball. Basketball players have an innate tendency to believe in the hot hand, even though it doesn't exist, so much so that it actually hurts their performance.

Why would the hot hand exist when it comes to predicting the future? What laws of physics would allow someone to predict the future better at some times rather than others? A gambler, regardless of skill level, will occasionally have hot streaks or cold streaks based on chance alone. So a gambler on a hot streak shouldn't change what type of bets they take, or how much they wager, just like NBA players shouldn't change what type of shots they take. But they do.

The problem with props

They suggested a bunch of prop bets. 5 of the 6 suggested were overs -- bets on players scoring at least one touchdown, or going over a certain number of yards. 4 out of 5 of the overs lost.

Gamblers greatly prefer betting the over on prop bets, which creates a problem. There's little to no money wagered on the under, which means gamblers taking the over are betting against the house, not other gamblers. That should be a warning sign. Sportsbooks are rational economic engines. If they're taking on more risk in the form of one-sided bets, they're going to want more reward in the form of a higher profit margin.

For a lot of prop bets, the big sportsbooks don't even allow taking the under. If a gambler can bet both sides, at least we can calculate the overround, or profit margin on the bet. With one-sided bets like these, there's no way to know how juiced the lines are (my guess would be to Buster Bluth levels.)

Traditionally, a sportsbook wants to have equal action on both sides of a bet. They don't really care what the line is. As long as the money's basically even (they have made a book), they can expect to make money no matter which team comes out on top.

With these one sided prop bets, there's no way for the free market to move the price by people betting the under instead. So the line doesn't need to be that close to the actual odds. Without action on both sides, sportsbooks have to be extremely vigilant about never setting an inaccurate line that gives the over too much of a chance of winning. And I don't think that gamblers taking overs on prop bets are too price sensitive. So the sportsbooks have multiple reasons to make the overs a bad deal.

Even sportsbooks that offer unders charge a huge amount of vig on prop bets to offset the additional uncertainty to the sportsbook. There are so many prop bets on each game relative to the number of people who take them. They can get away with setting the lines algorithmically because the lines don't need to be all that accurate with a bunch of extra juice on top.

This screenshot is from an offshore "reduced juice" sportsboook that allows bets on the unders.

We can convert the lines to win probabilities and add them up to calculate the overround, as covered a couple of articles ago.

For the Saquon Barkley bet, the overround is 8.9%. For Hurts it's 8.3%, for Brown it's 7.4%, and 7.9% for Smith.

The overround for a normal spread bet is 4.5%. We saw it's about the same with NBA money lines. Because this book is reduced juice, overrounds on spread bets are around 2.6% -- for instance odds of -108/-102 or -105/-105 instead of -110/-110.

Prop bets have 2x the juice of a traditional spread bet, and over 3x reduced juice. That requires the gambler to win far more often just to break even.

Ways to potentially reduce bias

I've previously written about an experiment that showed gamblers tend to take the favorite, even when they've been told it's a worse bet than the underdog. That wasn't true of the Ringer teams last week. They only took 11 favorites out of 25, so they didn't show that particular bias. But I think the experiment gives a hint how to reduce bias in general.

The researchers found that people could be corrected of their bias towards favorites by writing out what they thought the lines should be before seeing what the lines were. It causes the person to actually try and do the math problem of whether the bet is a good investment or not, rather than anchoring on the price set by the market, and picking the better team, or the conventional wisdom.

It would be interesting to try having each team member decide what the fair line was, then average them out. Do predictions made that way perform better?

Similarly, it would be helpful to convert any odds from the American style (like +310, or -160) to the equivalent probability. People who have gambled a lot might have an intuitive sense of what -160 means, but for me, the equivalent 61.5%, or "about 5/8" is much clearer. I can imagine a large pizza missing 3 of the 8 slices.

Betting jargon and betting superstitions should be avoided. Does each bet make sense as a financial transaction? Personal feelings and the enjoyability of the bet shouldn't factor in. The quality of the game and who is playing in it shouldn't matter.

The bottom bun

Despite not being a gambler, the gambling podcasts I listened to were fairly enjoyable. It's basically Buddies Talk About Sports, which is a pleasant enough thing to have on in the background. Nobody would listen to Casey's Rational Betting Show, for multiple reasons.

The Mathletix Bajillion, week 2

The Ringer crew had a good week, collectively going 14-11 (56%). One team out of five is now in the green. mathletix still won the week, winning 60% of our bets.

As a reminder, one set of picks is generated algorithmically, the other randomly. I'll reveal which one at the end of the competition.

"line shopping" refers to how much money was saved, or extra money was gained, by taking the best odds available instead of betting at a retail sportsbook.

All lines as of Friday morning.

The Neil McAul-Stars

last week: 5-0, +504

line shopping: +4

- LAC -3 +100 (prophetX)

- TB +5.5 +100 (lowvig)

- MIN -3 +105 (lowvig)

- ARI +3 -101 (prophetX)

- SEA +3.5 -111 (prophetX)

The Vincent Hand-eggs

last week: 1-4, -334

line shopping: +6

- LAR -3 -110 (hard rock)

- SF -3 -101 (prophetX)

- DET +2.5 +100 (lowvig)

- TEN +6 -107 (prophetX)

- GB -7 -105 (prophetX)