Nov 14, 2025

Song: Scientist, "Plague of Zombies"

This is a departure from the usual content on here, in that there's no real math or analysis. There's also not much of an audience for this website yet, so I hope you'll indulge me this week.

I was curious what all these gambling shows talk about for hours, when the picks they produce collectively appear to be no better than randomly chosen. I'm always interested in how people make decisions. How does their process work for choosing what bets to take? How might it work better?

Before I get too far into this, I know I'm being a killjoy. These podcasts are for entertainment purposes, just like betting is entertainment for a lot of people, not a sincere attempt to make money over the long term. Some degenerate gambling behavior is part of the appeal of these podcasts. They're selling the idea that "gambling is fun" as much as any particular bets.

It's still weird to be a gambling expert who can't do better than a coin flip.

I previously showed how combining multiple machine learning algorithms thru voting will only improve results when they make independent mistakes, and are significantly better than guessing. Those are both pretty intuitive conditions, and I think they're true of groups of people as well. If everybody has the same opinion, or makes the same sort of mistakes, or nobody really knows anything, there can't be a wisdom of crowds.

Humans have a big advantage over combining machine learning algorithms. We can talk with each other, challenge each others' assumptions, provide counterexamples, and so on.

There's not a ton of that in the gambling podcasts I listened to. Gambling talk is all about inventing stories about the future. It's sort of a competition for who can pitch the best narrative for the game. These stories are almost their own literary genre, and the construction of these are more important than the picks themselves. There aren't a lot of opportunities for the wisdom of crowds or some sort of error correction to occur.

Imagine I had a magic black box that was right about NBA lines 56% of the time. I could sell those picks, and be one of the better handicappers on the internet. While I could certainly write a little story for each one, maybe in the style of Raymond Carver -- "Will You Please Take The Over, Please?" -- the story doesn't make the bet more likely to be true, though, right? A factual story would be the same for every bet, and not very interesting: "there is slightly more value on this side of the bet, according to the model."

What we talk about when we talk about sports betting

Gambling personalities are always talking about what has happened in the past -- connections to previous games they've bet on, dubious historical trends, and the tendencies of certain players. Interactions like, "I thought you had a rule never to bet against Baker Mayfield?" "But he's 2-7 on the road in early Sunday games after a Monday night game where he got over 30 rushing yards."

These arbitrary connections remind me of a bit from Calvino's Invisible Cities:

In Ersilia, to establish the relationships that sustain the city's life, the inhabitants stretch strings from the corners of the houses, white or black or gray or black-and-white according to whether they mark a relationship of blood, of trade, authority, agency. When the strings become so numerous that you can no longer pass among them, the inhabitants leave: the houses are dismantled; only the strings and their supports remain.

There were quite a few of those useless strings in the November 6th episode of the Ringer Gambling Show.

The top bun

On a couple of occasions, the show discussed whether certain information was already priced into the line or not. Since gambling should be about determining which bets have positive expected value, that's a very useful thing to discuss. "If this spread looks wrong, what does the market know that we don't? Or what do we know that the market doesn't?"

If the goal is to win, the implicit question should always be: why do we think we have an advantage over other gamblers taking the other side? Why are we special? Why do we think the line isn't perfect?

Superstitions and biases

They were resistant to bet on teams that they had recently lost money on -- not wanting to get burned again. This is clearly not a financial choice, but an emotional one. The axe forgets, the tree remembers.

Team loyalty also affected their betting decisions. They avoided taking Baltimore because Ariel is a Ravens fan (the bet would have won). Jon suggested betting against his team, the Dolphins, which Ariel jokingly called "an emotional hedge". The Dolphins won. So they cost themselves two potential wins due to their fandom.

They decided not to take a bet on Houston (which ended up winning) because, in Jon's words, "betting on Davis Mills is not a pleasant experience". Whether a team or player was fun to bet on came up a couple of other times as well. Someone just trying to make a profit wouldn't care how fun the games are to watch. They might not even watch the games at all. Whether the gambler watches the game or not has no influence on the outcome.

Bets need to be fun, not just a good value. These gambling experts still want to experience "the sweat" -- watching the game and rooting for their bet to win. As I wrote last week, betting on the Browns and losing is like losing twice, so even if the Browns are a better value, they are a bad pick for emotional reasons. Who wants to have to be a Browns fan, if only for a few hours?

It's sort of like Levi-Strauss said about food. It's not enough that a type of food is good to eat, it must also be good to think about. The Houston Texans led by Davis Mills are not "bon à penser".

Not enough useful disagreement

All three of the bets they were in total agreement on (PIT, TB, ARI) lost. Nobody presented a case against those bets, so there was no opportunity for any of them to change their minds or reconsider their beliefs.

I'm not endorsing pointless contrarianism -- not every side needs to be argued. Don't be that one guy in every intro to philosophy class. But if both sides of an issue (or a bet) have roughly equal chances of being true, there should be a compelling case to be made for either side. Someone who can't make both cases fairly convincingly probably doesn't know enough to say which case is stronger.

Two types of hot streaks

For gamblers, there's one type of hot streak that's always bound to end. A team has won a few games it shouldn't have won, therefore they're bound to lose the next one. Their lucky streak will fail. In the real world, there's no invisible hand that pulls things down to their averages on a set schedule. In a small sample size of 17 games in an NFL season, there's no reason to think things will be fair by the end, much less the very next game. Now, a team could be overvalued by the market because they got some lucky wins, which makes them a value to bet against. But teams don't have some fixed number of "lucky games" every year, and once they've burned through those, their luck has to turn.

The other type of hot streak is bound to keep going. The team were divided whether to bet the Rams or not. They decided to go with Ariel's opinion, because she's been on a hot streak lately. If Ariel's record was demonstrably better than the other two hosts' over a long period of time, it would make sense deferring to her as the tiebreaker. But winning a few bets in a row doesn't mean the next bet is any more likely (or less likely) to win. As a teammate, that's a supportive thing to do, so I'm sure that's part of it. But people who gamble tend to think they have it sometimes, and don't have it other times. Sometimes they're hot, sometimes they're cold.

We've seen this before with NBA basketball. Basketball players have an innate tendency to believe in the hot hand, even though it doesn't exist, so much so that it actually hurts their performance.

Why would the hot hand exist when it comes to predicting the future? What laws of physics would allow someone to predict the future better at some times rather than others? A gambler, regardless of skill level, will occasionally have hot streaks or cold streaks based on chance alone. So a gambler on a hot streak shouldn't change what type of bets they take, or how much they wager, just like NBA players shouldn't change what type of shots they take. But they do.

The problem with props

They suggested a bunch of prop bets. 5 of the 6 suggested were overs -- bets on players scoring at least one touchdown, or going over a certain number of yards. 4 out of 5 of the overs lost.

Gamblers greatly prefer betting the over on prop bets, which creates a problem. There's little to no money wagered on the under, which means gamblers taking the over are betting against the house, not other gamblers. That should be a warning sign. Sportsbooks are rational economic engines. If they're taking on more risk in the form of one-sided bets, they're going to want more reward in the form of a higher profit margin.

For a lot of prop bets, the big sportsbooks don't even allow taking the under. If a gambler can bet both sides, at least we can calculate the overround, or profit margin on the bet. With one-sided bets like these, there's no way to know how juiced the lines are (my guess would be to Buster Bluth levels.)

Traditionally, a sportsbook wants to have equal action on both sides of a bet. They don't really care what the line is. As long as the money's basically even (they have made a book), they can expect to make money no matter which team comes out on top.

With these one sided prop bets, there's no way for the free market to move the price by people betting the under instead. So the line doesn't need to be that close to the actual odds. Without action on both sides, sportsbooks have to be extremely vigilant about never setting an inaccurate line that gives the over too much of a chance of winning. And I don't think that gamblers taking overs on prop bets are too price sensitive. So the sportsbooks have multiple reasons to make the overs a bad deal.

Even sportsbooks that offer unders charge a huge amount of vig on prop bets to offset the additional uncertainty to the sportsbook. There are so many prop bets on each game relative to the number of people who take them. They can get away with setting the lines algorithmically because the lines don't need to be all that accurate with a bunch of extra juice on top.

This screenshot is from an offshore "reduced juice" sportsboook that allows bets on the unders.

We can convert the lines to win probabilities and add them up to calculate the overround, as covered a couple of articles ago.

For the Saquon Barkley bet, the overround is 8.9%. For Hurts it's 8.3%, for Brown it's 7.4%, and 7.9% for Smith.

The overround for a normal spread bet is 4.5%. We saw it's about the same with NBA money lines. Because this book is reduced juice, overrounds on spread bets are around 2.6% -- for instance odds of -108/-102 or -105/-105 instead of -110/-110.

Prop bets have 2x the juice of a traditional spread bet, and over 3x reduced juice. That requires the gambler to win far more often just to break even.

Ways to potentially reduce bias

I've previously written about an experiment that showed gamblers tend to take the favorite, even when they've been told it's a worse bet than the underdog. That wasn't true of the Ringer teams last week. They only took 11 favorites out of 25, so they didn't show that particular bias. But I think the experiment gives a hint how to reduce bias in general.

The researchers found that people could be corrected of their bias towards favorites by writing out what they thought the lines should be before seeing what the lines were. It causes the person to actually try and do the math problem of whether the bet is a good investment or not, rather than anchoring on the price set by the market, and picking the better team, or the conventional wisdom.

It would be interesting to try having each team member decide what the fair line was, then average them out. Do predictions made that way perform better?

Similarly, it would be helpful to convert any odds from the American style (like +310, or -160) to the equivalent probability. People who have gambled a lot might have an intuitive sense of what -160 means, but for me, the equivalent 61.5%, or "about 5/8" is much clearer. I can imagine a large pizza missing 3 of the 8 slices.

Betting jargon and betting superstitions should be avoided. Does each bet make sense as a financial transaction? Personal feelings and the enjoyability of the bet shouldn't factor in. The quality of the game and who is playing in it shouldn't matter.

The bottom bun

Despite not being a gambler, the gambling podcasts I listened to were fairly enjoyable. It's basically Buddies Talk About Sports, which is a pleasant enough thing to have on in the background. Nobody would listen to Casey's Rational Betting Show, for multiple reasons.

The Mathletix Bajillion, week 2

The Ringer crew had a good week, collectively going 14-11 (56%). One team out of five is now in the green. mathletix still won the week, winning 60% of our bets.

As a reminder, one set of picks is generated algorithmically, the other randomly. I'll reveal which one at the end of the competition.

"line shopping" refers to how much money was saved, or extra money was gained, by taking the best odds available instead of betting at a retail sportsbook.

All lines as of Friday morning.

The Neil McAul-Stars

last week: 5-0, +504

line shopping: +4

- LAC -3 +100 (prophetX)

- TB +5.5 +100 (lowvig)

- MIN -3 +105 (lowvig)

- ARI +3 -101 (prophetX)

- SEA +3.5 -111 (prophetX)

The Vincent Hand-eggs

last week: 1-4, -334

line shopping: +6

- LAR -3 -110 (hard rock)

- SF -3 -101 (prophetX)

- DET +2.5 +100 (lowvig)

- TEN +6 -107 (prophetX)

- GB -7 -105 (prophetX)

Nov 07, 2025

Song: Charlie Musselwhite, "Cristo Redentor"

Are betting experts any good at what they do?

These days, nearly all talk about gambling I see on TV and the internet is sponsored by one of the sportsbooks. How good is all this sponsored advice?

There are quite a few shows that are just about gambling, but more common are ad reads from Youtubers or sportscasters who are sponsored by sportsbooks, but aren't really focused on gambling. These appear on-air in the middle of a game, or an ad break in a Youtube video.

Picks from sports announcers do terribly, as the Youtube channel Foolish Baseball has documented in their wonderful video, Baseball is Ruining Gambling.

As a numbers guy, it's baffling that anybody would follow these obviously sponsored picks at obviously juiced lines, given by obviously casual gamblers, but some people are taking them, because the sportsbooks keep paying for the ads.

Gambling is a social and parasocial activity now, another thing you do on your phone when you're bored that sort of feels like interacting with other humans, but isn't.

Some gamblers want to be on the same side of the bet as their favorite YouTuber, who give their favorite picks as a part of an ad read. The apps also allow you to follow people, and take the same bets they take. It's yet another one-way online relationship.

Other gamblers take bets to feel more connected to their team. Announcer parlays are invitations to take a financial interest in the game that you're already watching, not necessarily because you think the Brewers play-by-play guy is secretly a betting wizard. The baseball announcers don't seem to have much of an interest in gambling, or being touts. They're not there for our wholesome national pastime, gambling on sports, they're true sickos who are only interested the disreputable game of baseball. Putting together some half-ass parlay for the promo is part of their job. It's just another ad read. It may as well be a local roofing company or a personal injury lawyer.

Sportsbooks advertise because it makes them money in the long run. These companies seem pretty well-run, if nothing else. They want to sponsor people who are good at bringing in customers with a high Customer Lifetime Value -- people who will lose over and over again for years, making back the cost to acquire them as a customer many times over. That's it. That's the game. Why would they sponsor people who give good advice about gambling, or good picks?

Do people care whether gambling experts are actually good or not?

Some guys talk about gambling for a living. They discuss sports from the perspective of people who are gamblers first, and sports fans second. Everything's an angle, or a trend, or a bad beat. At the extreme, athletic competitions are interesting because betting on them is interesting, not because sports themselves are. These guys are both living and selling the gambling lifestyle, which I talk much more about in the book:

A parasocial relationship with a guy selling picks or talking about gambling on a podcast causes guys to want to form social relationships around gambling. They're Gambling Guys now. Which leads to an endless parade of dudes complaining about their parlays online, and, I would wager, annoying the heck out of their significant others. "It's a whole lifestyle, Sherri! Of course I had to get my tips frosted! I'm a Gambling Guy now!"

It's all imaginary. An imaginary relationship with a betting guru in the form of a "hot tip". An imaginary relationship with the sporting event or player in the form of a bet. An imaginary relationship with reality itself in the form of the rationalization about why the "hot tip" didn't win. An imaginary relationship between winning and skill.

Being a sports fan is already ridiculous enough.

Poking the bear, a bit

The Ringer is a website about sports and pop culture that has evolved into a podcasting empire. I like a lot of what they do, and I especially appreciate that they publish great writing that surely isn't profitable for the company. For the most part, I can just enjoy their non-gambling content and ignore that it's subsidized by gambling.

But they've done as much as anyone to normalize sports betting as a lifestyle, and deserve an examination of that. The Ringer wasn't worth a bajillion dollars before gambling legalization, back when they were doing MeUndies ad reads.

The Ringer has an incredible amount of content that's just Gambling Guys Talk Gambling with Other Gambling Guys, around 10 hours a week of podcasts, by my count. The Ringer's flagship show is the Bill Simmons Podcast, which usually devotes at least a couple hours a week to discussing which bets Bill and his pals think are good. (Previously satirized in Cool Parlay, Bro)

The site also has an hour long daily podcast about gambling, The Ringer Gambling Show, and several other podcasts that regularly discuss betting. As far as I know, all of their sports podcasts feature gambling ad reads, even the ones with hosts that clearly find gambling distasteful.

Several members of the Ringer's staff are full time Gambling Guys now. They talk about their addictions for a living, which must be nice. I've been talking about my crippling data science addiction on here for months without a single job offer.

Are these guys good at their job, though? (Are they good at their addictions?) The Ringer is currently having a contest betting on the NFL between five different NFL podcasts, four of which primarily cover sports gambling, which they're calling The Ringer 107. Here are their results through Week 9:

Every single one of the five teams is losing money against the spread. They don't make it clear on the website, but some bets are at -120 vig, so the records are even worse than they look.

It might be bad luck, right? I've written at length about how having a true skill level of 55% doesn't guarantee actually winning 55% of the bets.

Based on this data, it's extremely unlikely the gambling pros at the Ringer are just unlucky. I simulated 5 teams taking the same number of bets as the Ringer's contest so far. If every pick had a 55% chance of winning (representing picks by advantage players), then 99.5% of the time, at least one team does better than all five of the Ringer's did.

Even at a 50% winning rate, same as flipping a coin, the simulation does better than the Ringer 91% of the time. Based on this data, you'd be better off flipping a coin than listening to these gambling experts.

The easiest way to know they can't do it

If I talked about gambling for a living and was demonstrably good at it, I'd want everyone to see the proof. These guys almost never post their actual records over a long stretch of time, though. They will crow about their wins, and offer long-winded explanations as to why their losing picks were actually right, and reality was wrong. But it's hard to find actual win-loss records for them.

Last season, The Ringer's Anthony Dabbundo didn't appear to keep track of his record betting on the NFL against the spread at all (example article). This year, he has, so we know he's gone 37-37, and 20-25 on his best bets, despite some of them being at worse than -110 odds. His best bets have had a return of -16.7%, about the same as lazy MLB announcer parlays, and almost 4 times worse than taking bets by flipping a coin.

What odds would you give me that the Ringer goes back to not showing his record next season?

To be clear, I don't think Dabbundo is worse than the average gambling writer at gambling. I've never found a professional Gambling Guy that is statistically better than a coin flip. Dabbundo's job is writing/podcasting the little descriptions that go along with each of his picks. His job isn't being good at gambling, it's being good at talking about gambling. There is no evidence that he can predict the future but plenty of evidence he can crank out an hour of podcast content every weekday that enough people enjoy listening to. Predicting the future isn't really the value-add for these sorts of shows.

The curse of knowledge

I think it's significant that by far the worst team in the contest is the Ringer NFL Show, which is primarily not about gambling. It's a show by extreme football nerds, for extreme football nerds. Once in a while I listen to it while doing the dishes, and I'll go like 20 minutes without recognizing a single player or football term they're talking about. They are all walking football encyclopedias, as far as I'm concerned.

If gambling really were a matter of football-knowing, they should be winning. They aren't, because betting isn't a football-knowing contest.

I can see how being a true expert might make somebody worse at gambling. Every bet is a math problem, not a trivia question. A bet at a -4.5 spread might have a positive expected value, but a -5.5 spread have a negative expected value. People who are good at sports gambling can somehow tell the difference. Like life, sports gambling is a game of inches.

The folks on the Ringer NFL Show know the name of the backup Left Tackle for every team in the league, but I don't think that's really an advantage in knowing whether -4.5 or -5.5 is the right number for a particular game. Most of the cool football stuff they know should already be baked into the line, or is irrelevant. Sports betting is a lot more like The Price Is Right than it is like sports.

A great chef might know practically everything there is to know about food. They might know what type of cheese is the tastiest, how to cook with it, and so on. But if they went to the grocery store, that doesn't mean they would notice that they had gotten charged the wrong price for the cheese, or that they could get it 20% cheaper at another store. That's a totally different skillset and mindset.

People on these gambling shows spend several minutes explaining each of their picks, listing lots of seemingly good reasons. I think that having to give a good reason for each pick forces them into going with what they know, not considering that all the obvious information and most of the non-obvious information they have is already reflected in the line. Needing to be seen as an expert could lead them to pick the side with slightly less value on it, because they want to make a defensible pick. It's much better to have a good sounding reason for making a pick, and losing, than it is to have no reason for making a pick and winning.

In general, I think every bet has a more reasonable side and a crazier side. Anybody prognosticating for a living has a disincentive to pick the crazier side if they're going to have to explain the bet if they happen to lose. It doesn't if there was actually more value than the Browns. Losing on the Browns and then having to live with being the guy who bet on the Browns is two losses at once.

The Mathletix Bajillion, week 10

I figured I should take a crack at it. The season is mostly over, so it will be a small sample size, but let's see what happens. At the very least, it will force me to publish something at least once a week for the next couple of months, and if things go bad, work on developing the shamelessnesss of someone who gets paid to predict the future, even though they can't.

I'm going to make two sets of picks, one based on a proprietary betting model I created, the other purely random, based on rolling dice. At the end, I will reveal which team is which, and see how they do against the Ringer's teams.

I am an extremely casual fan of the NFL, so little to no actual ball-knowing will go into these picks. I probably know less about football than the average person who bets on football. I don't think that's really a disadvantage when the football experts are going 18-27 on the year.

I will take all bets at -110 odds or better. No cheeky -120 bets to goose the win-loss record a bit, like some of the teams in the Ringer competition have done. But I will also shop around between sportsbooks and take the best lines I can find, by checking sites like unabated, reduced juice sportsbooks like lowvig and pinnacle, and betting exchanges like matchbook and prophetx.

For the betting exchanges, I will only take spreads where there is at least $1000 in liquidity -- no sniping weird lines. Part of what I'm trying to show is that bargain shopping, which has nothing to do with football knowledge, can make a big difference. So I will shop pretty aggressively. Even if I lose, I will lose less fake money than I would at -110, which means I don't have to win as often to be profitable. I'm pretty confident I can beat the Ringer pros on that point at least.

Sources will be noted below.

Team names come from the 1995 crime drama Heat, starring Tom Sizemore, in accordance with the Ringer house style.

Picks were made Friday evening.

The Neil McAul-Stars

- ATL +6.5 -108 (fanduel)

- NO +5.5 -109 (prophetx)

- SEA -6.5 -110 (prophetx)

- PHI +2 -109 (Rivers)

- LAC -3 +104 (prophetx)

The Vincent Hand-eggs

- DET -7.5 -105 (prophetx)

- PIT +3 -109 (prophetx)

- TB -2.5 -110 (fanduel)

- CHI -4.5 -105 (fanduel)

- CAR -5 -110 (harp rock casino)

Nov 05, 2025

Song: Geraldo Pino, "Heavy Heavy Heavy"

Code: https://github.com/csdurfee/scrape_yahoo_odds/. See the push_charts.ipynb notebook.

NBA Push Charts

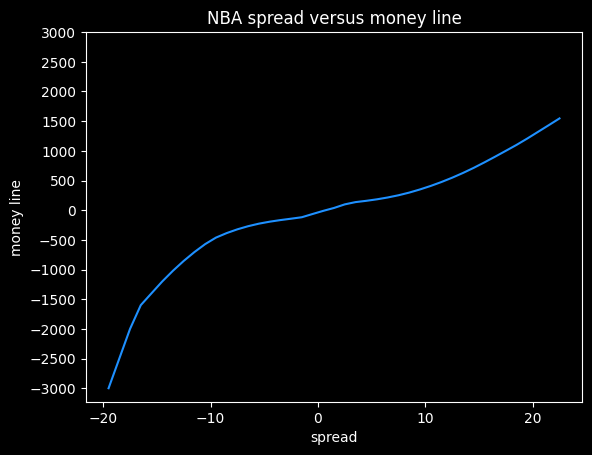

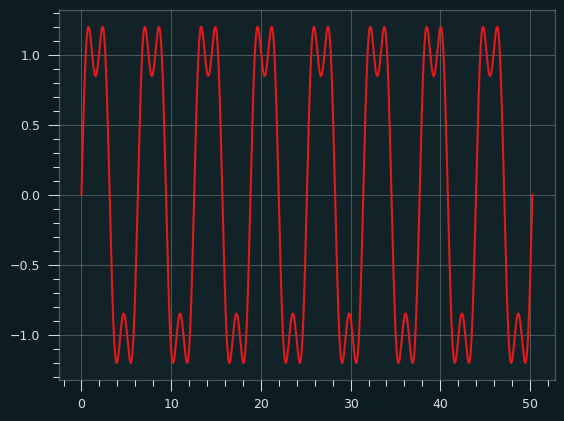

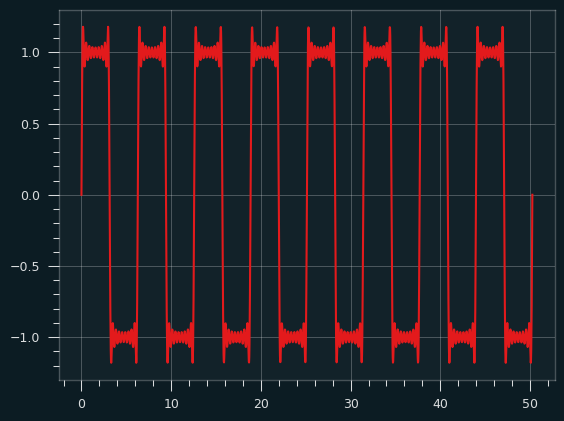

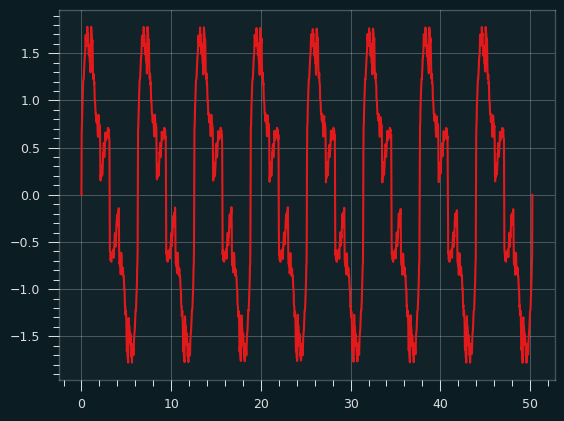

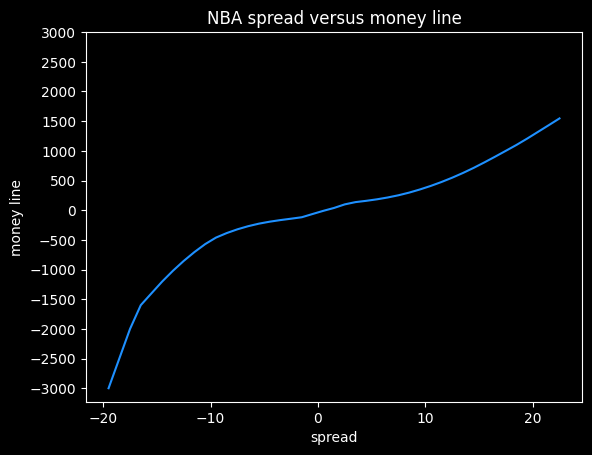

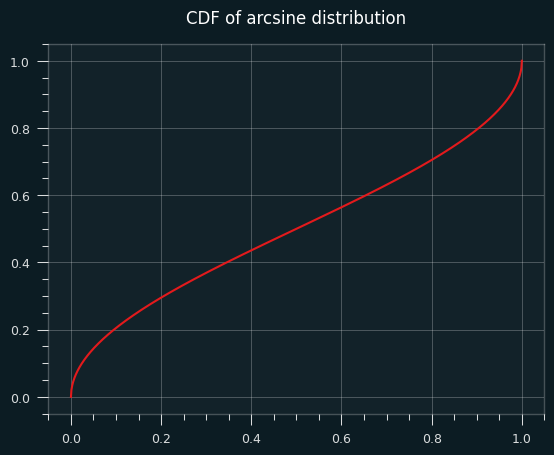

In the past couple of posts, I've looked at NBA betting data from BetMGM. There are multiple types of bets available on every game. A push chart maps the fair price of a spread bet to the equivalent money line bet. How often does a team that is favored by 3 points win the game outright? It's going to be less often than a team favored by 10 points. The money line should reflect those odds of winning.

You can find a lot of push charts online, but they tend to be based on older NBA data. With more variance due to a lot of 3 point shots, and more posessions per game, I wouldn't expect them to still be accurate.

Push charts are useful for assessing which of two different wagers is the better value. Here's an example of a game where different sportsbooks have different lines for the same game:

Say you want to bet on the Warriors. They have some players out tonight (Nov 5, 2025) so they're the underdogs, but they are also playing the dysfunctional Kangz, so it might be a good value bet. You could take the Warriors at either +3.5 -114, +3 -110, or +2.5 -105. Which bet has the highest expected value? If the Warriors lose by 3, the +3.5 bet would win, but the +3 bet would push (the bet is refunded), and the +2.5 bet would lose. A push chart can give a sense of how valuable the half points from +2.5 to +3, and +3 to +3.5, are. Is the probability of the Warriors losing by exactly 3 -- the value of getting a push -- worth going from -105 to -110?

[edit: the Warriors, without their 3 best players, led for most of the game before eventually losing by 5 after Russell Westbrook had one of his best games in years. So the line was only off by 2 points. The lines are often uncannily close, even when a bunch of weird stuff happens. Sometimes it all kinda cancels out.]

I'm going to do a push chart two different ways, then combine them. For almost every game over the last 4 years, we have the money line and the spread, so we can match them up directly. These will have the vig baked in. And as we saw previously, the money line for favorites has a slightly better expected value than the average bet on the spread. So it's going to end up a little biased.

We can also calculate a push chart without any vig by looking at winning percentage for every spread -- what percent of the time does a +3.5 point underdog actually win the game. It will need some smoothing, since the data will be noisy.

The retail NBA push chart

I matched up the spread and the money line for both the home and the away team on each game, then took the median of those values. Spreads in the range of -0.5 to +0.5 are very rare, as are spreads over -13.5/+13.5, so I've omitted those.

|spread |money line|

|------:|---------:|

| -13.5 | -1000 |

| -12.5 | -750 |

| -11.5 | -650 |

| -10.5 | -550 |

| -9.5 | -450 |

| -8.5 | -375 |

| -7.5 | -300 |

| -6.5 | -250 |

| -5.5 | -225 |

| -4.5 | -190 |

| -3.5 | -160 |

| -2.5 | -140 |

| -1.5 | -120 |

| 1.5 | 100 |

| 2.5 | 115 |

| 3.5 | 135 |

| 4.5 | 155 |

| 5.5 | 180 |

| 6.5 | 200 |

| 7.5 | 240 |

| 8.5 | 290 |

| 9.5 | 340 |

| 10.5 | 400 |

| 11.5 | 475 |

| 12.5 | 525 |

| 13.5 | 625 |

This gives us how BetMGM prices the value of individual points on the spread (with the vig figured in). This is sort of their official price list.

American style odds are symmetrical if there is no vig involved. A -400 bet implies a 4/5 chance of winning, and a +400 bet implies a 1/5 chance of winning. If the -400 bet wins 4/5 of the time and loses 1/5 of the time, the gambler breaks even, and vice versa. So a no-vig money line would be +400/-400.

The odds offered by the sportsbooks are asymmetrical, because they want to make money. We see that +13.5 on the spread maps to a +625 money line, but -13.5 maps to -1000. A +625 bet should win 100/(100+625), or about 14% of the time. A -1000 bet should win 1000/1100, or 91% of the time. Adding those together, we get 91% + 14% = 105%. That extra 5% is called the overround, and is the bookmaker's guaranteed profit, assuming they have equal wagers on both sides.

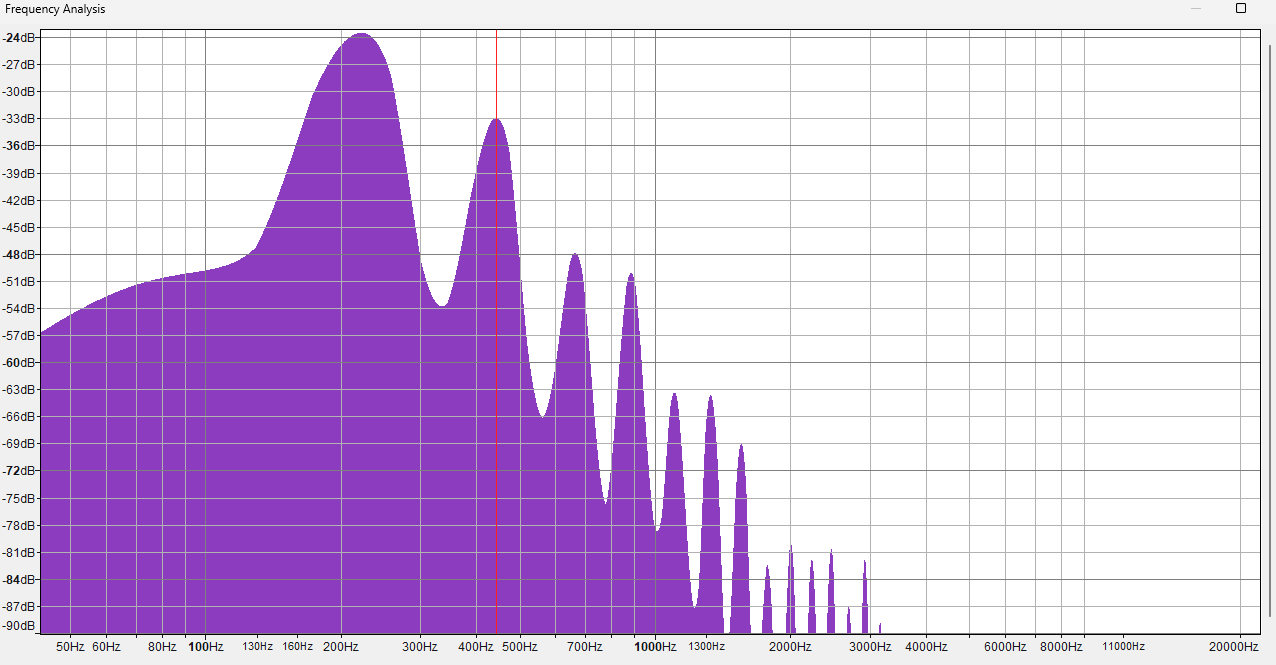

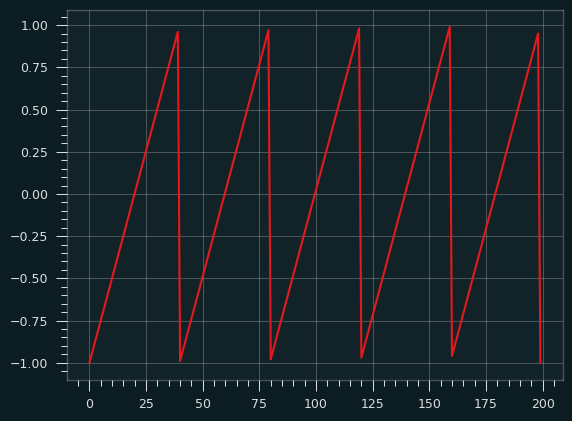

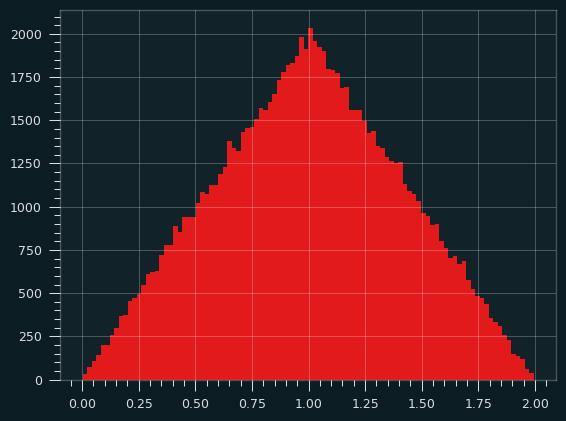

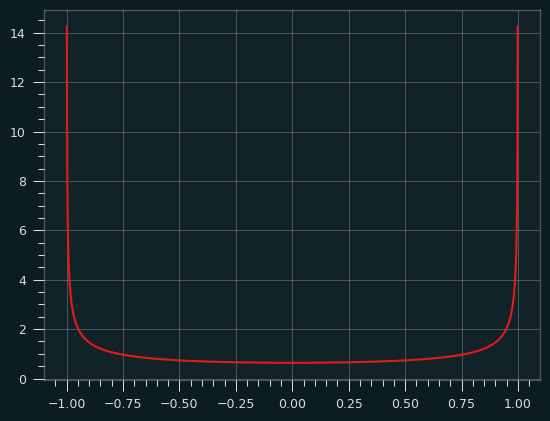

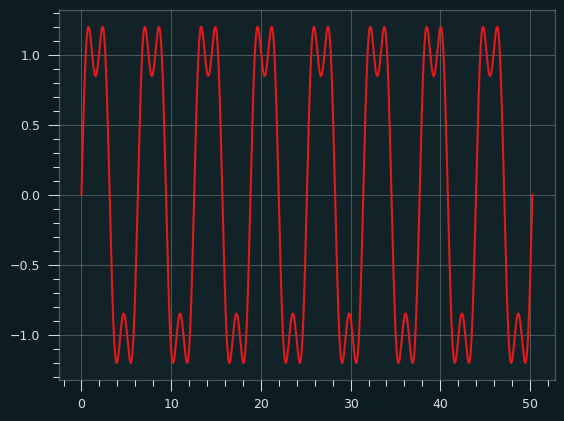

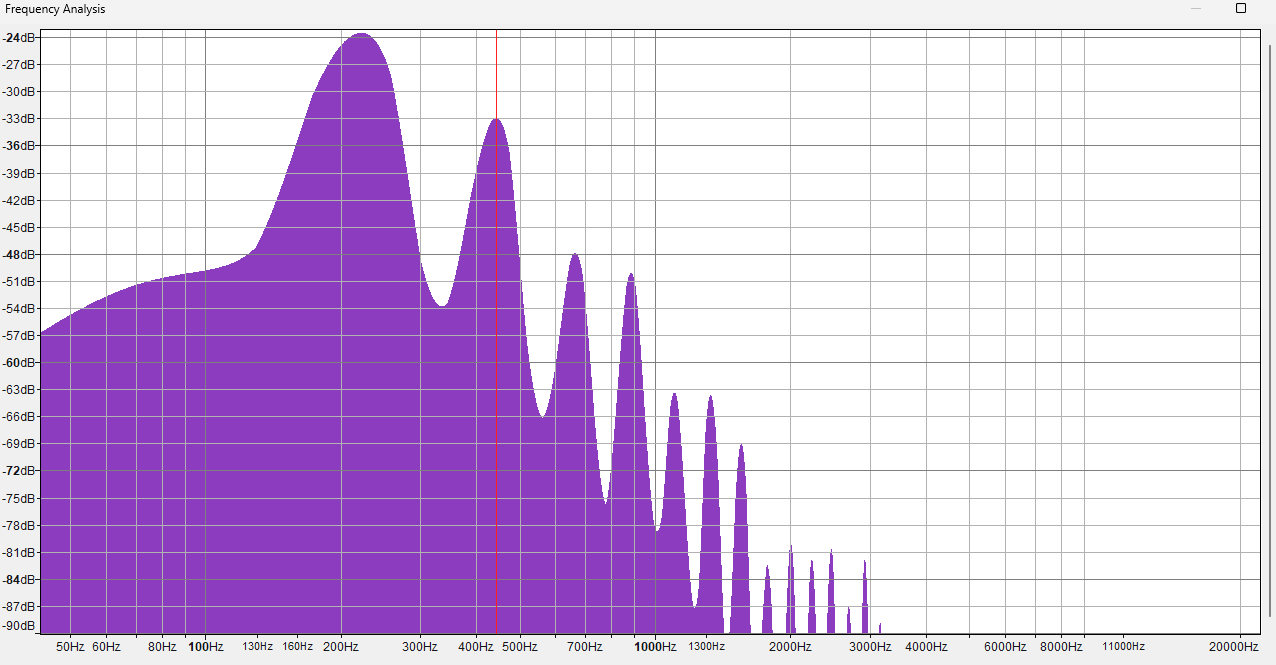

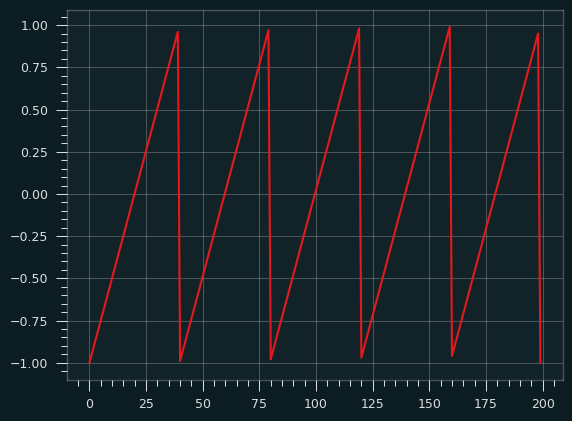

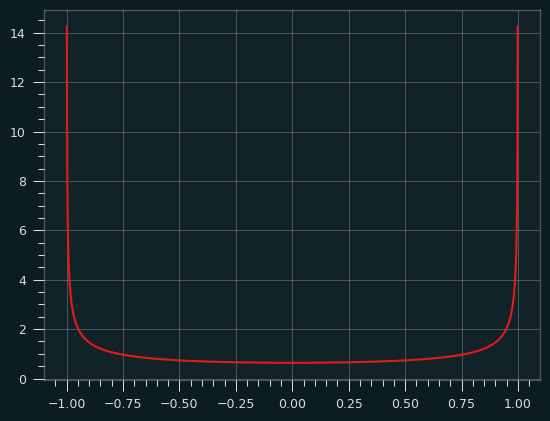

Here's what that data looks like as a graph, with some smoothing added.

I think this shows the bias against heavy favorites that we saw previously. Note how the line gets much steeper moving from -10 to -20 on the spread, versus moving from +10 to +20.

At -20.5, this graph gives a payout of -5000, but at +20.5, it gives a payout of +1320. The fair payout is somewhere in between those two numbers.

If the fair payout is (-5000/+5000), then the underdog is getting way less of a payout (in essence, paying more in vig) than they should. If the fair payout is closer to (-1360/+1360), then the favorite is paying more in vig than they should. So the asymmetricality gives a clue that sportsbooks aren't splitting the vig down the middle, but it doesn't tell us the fair price.

Push charts based on win frequencies

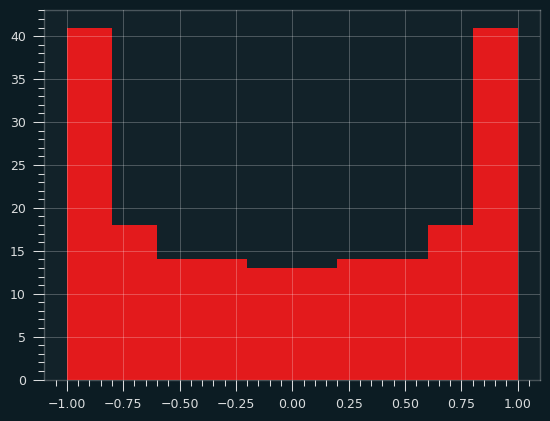

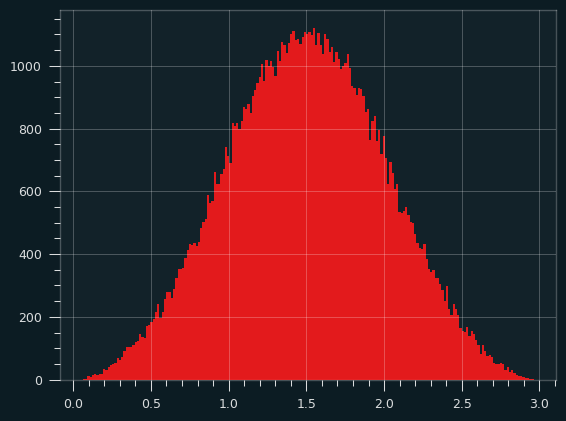

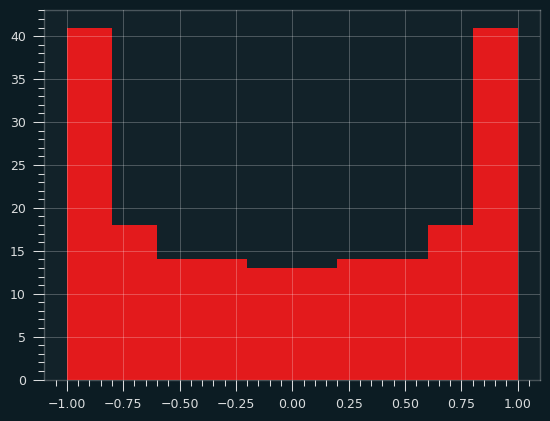

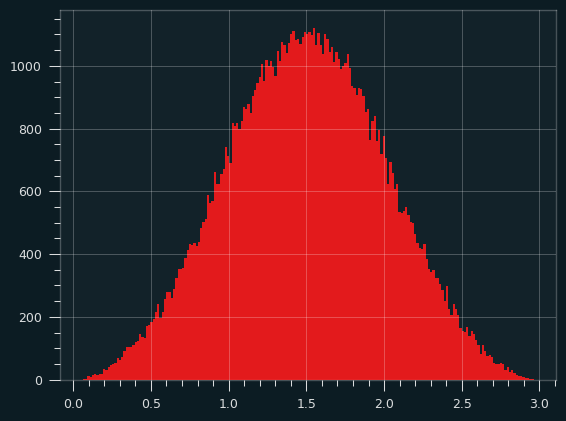

We can estimate a fair price by going through all the games and see how often a +3.5 underdog wins outright, then convert that percentage to a fair money line. The problem here is that the results will be very noisy. We'd need hundreds or thousands of games at each spread value, and we only have 4,500 or so games overall. So it's gonna be chunky. We'll have to do some smoothing on it, (foreshadowing alert: it will lead to weird results later on)

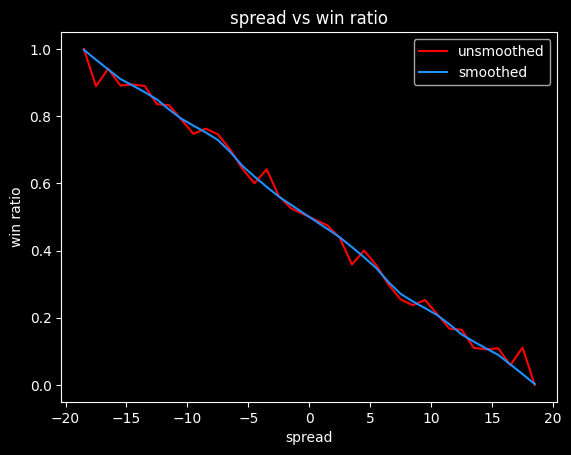

Here are the win ratios by spread, combining both home and away teams:

| spread| win ratio |

|------:|----------:|

| -13.5 | 0.889764 |

| -12.5 | 0.835616 |

| -11.5 | 0.832487 |

| -10.5 | 0.789474 |

| -9.5 | 0.747212 |

| -8.5 | 0.762763 |

| -7.5 | 0.745763 |

| -6.5 | 0.701299 |

| -5.5 | 0.643892 |

| -4.5 | 0.6 |

| -3.5 | 0.641682 |

| -2.5 | 0.562393 |

| -1.5 | 0.525535 |

| 1.5 | 0.474465 |

| 2.5 | 0.437607 |

| 3.5 | 0.358318 |

| 4.5 | 0.4 |

| 5.5 | 0.356108 |

| 6.5 | 0.298701 |

| 7.5 | 0.254237 |

| 8.5 | 0.237237 |

| 9.5 | 0.252788 |

| 10.5 | 0.210526 |

| 11.5 | 0.167513 |

| 12.5 | 0.164384 |

| 13.5 | 0.110236 |

A team with a -1.5 point spread wins 52.6% of the time, which is very close to the break-even point on standard -110 bets of 52.4%. So a gambler needs to be at least 1.5 points better than Vegas at setting the lines to expect to make money.

These odds have to be symmetrical. If a team favored by -4.5 wins 60% of the time, then a +4.5 point underdog has to win 40% of the time.

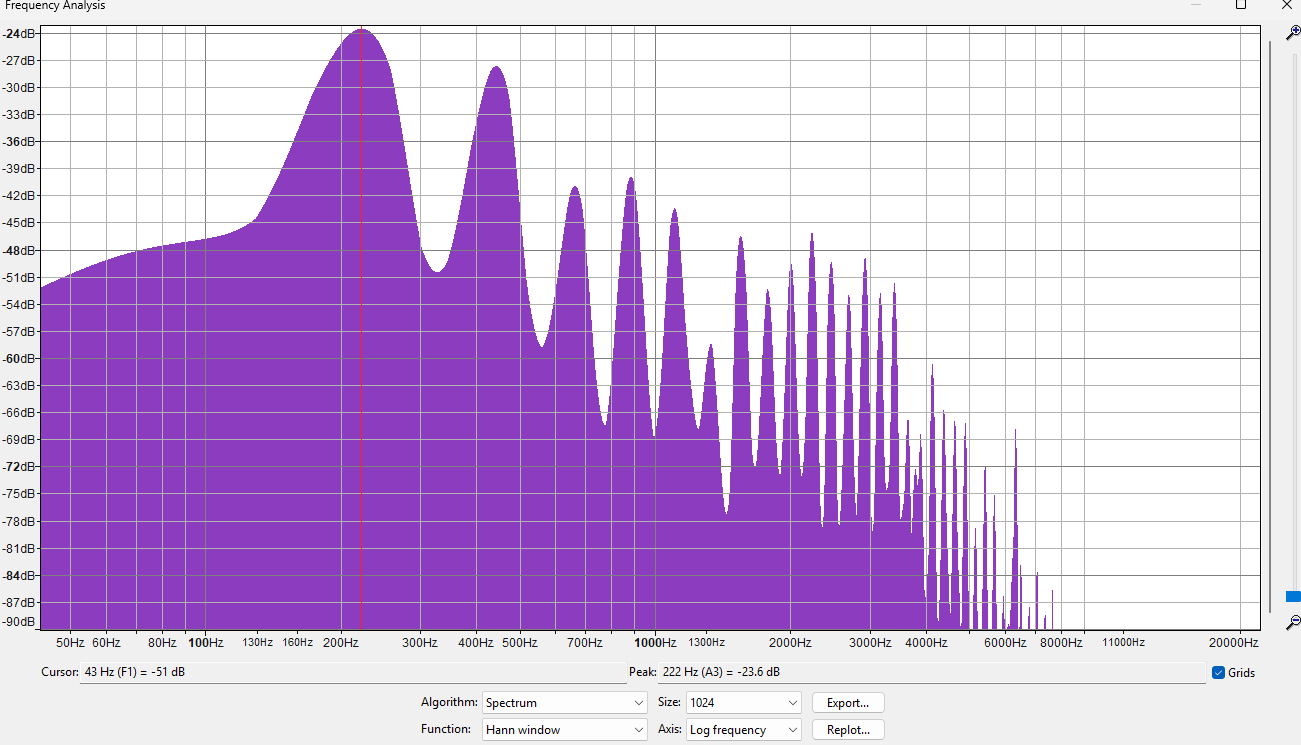

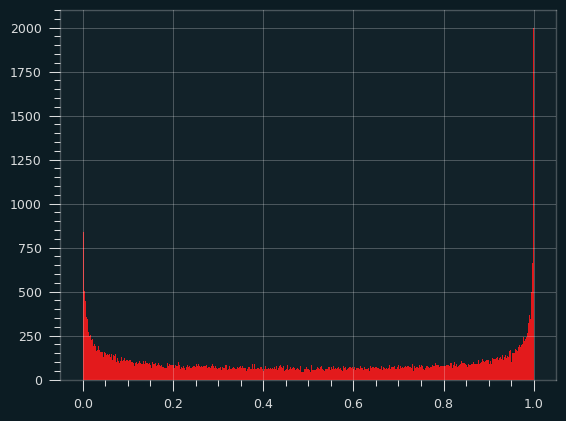

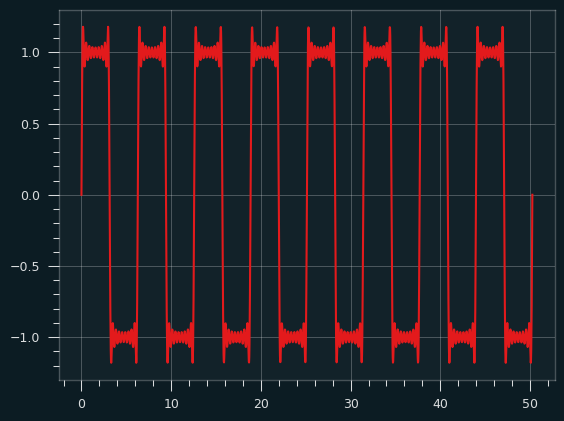

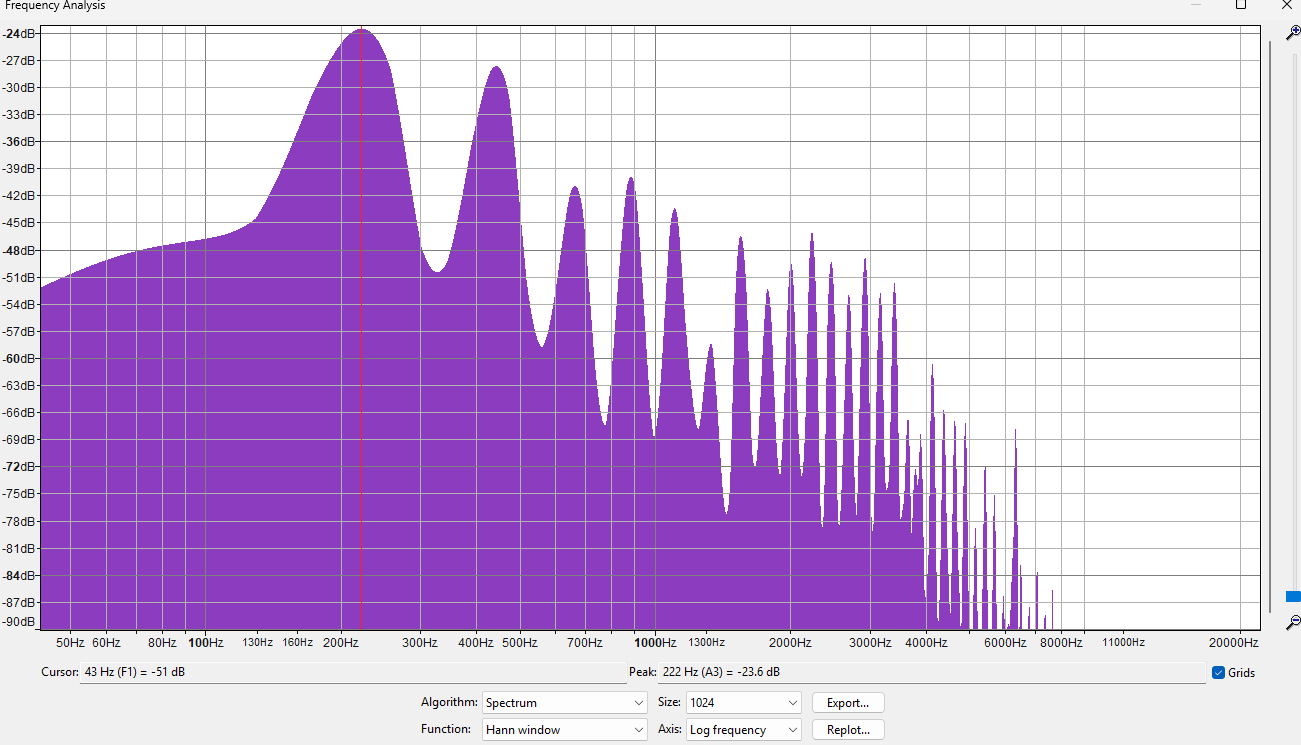

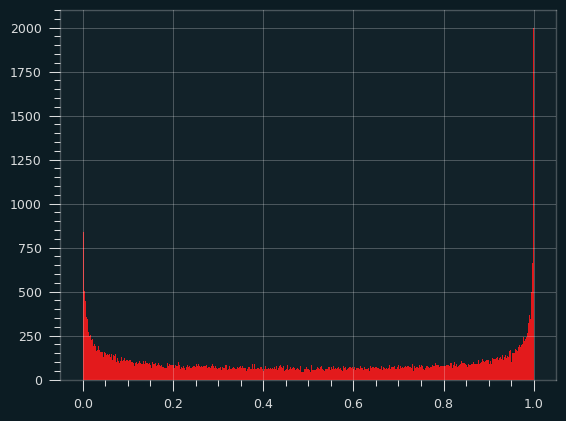

Unfortunately, this data is probably too chunky to give good results. -4.5 has a lower win rate than -5.5, which doesn't make any sense. The more negative the spread, the higher the win rate should be. Here's what it looks like with smoothing:

We can convert these winning percentages to fair (no vig) money lines:

Converting to money lines doesn't break the symmetry. A -4.5 favorite gets a money line of -163, and a 4.5 point underdog gets a money line of +163.

This is just a first attempt. Different ways of smoothing the actual win rates will lead to different results.

|spread |fair ML |

|------:|-------:|

| -13.5 | -677 |

| -12.5 | -565 |

| -11.5 | -454 |

| -10.5 | -381 |

| -9.5 | -338 |

| -8.5 | -303 |

| -7.5 | -269 |

| -6.5 | -227 |

| -5.5 | -188 |

| -4.5 | -163 |

| -3.5 | -144 |

| -2.5 | -128 |

| -1.5 | -116 |

| 1.5 | 116 |

| 2.5 | 128 |

| 3.5 | 144 |

| 4.5 | 163 |

| 5.5 | 188 |

| 6.5 | 227 |

| 7.5 | 269 |

| 8.5 | 303 |

| 9.5 | 338 |

| 10.5 | 381 |

| 11.5 | 454 |

| 12.5 | 565 |

| 13.5 | 677 |

Crossing the streams, and an abrupt ending

What happens if we look at the difference between the no-vig moneylines, and what the sportsbook actually charges? Will it show us the favorite-longshot bias?

It turns out, it doesn't. The win frequency data is too noisy. I spent a lot of time spinning my wheels on it, before realizing I didn't have enough data. I will come back to the subject, though, because failure is more educational than success.

Oct 26, 2025

Song: Pigeonhed, "Glory Bound" (Dave Ruffy Remix)

Code: https://github.com/csdurfee/scrape_yahoo_odds/

A little crowd wisdom

Last week, we saw that for NBA spread bets, the more popular side wins 49.2% of the time. This matches what I've shown before -- the public is generally worse than a coin flip when betting on NBA basketball.

This week, I have some good news. There are some types of bets on the NBA where the public do a little better than expected. Not enough to make money, but better than picking bets by flipping a coin.

Money line bets and rationality

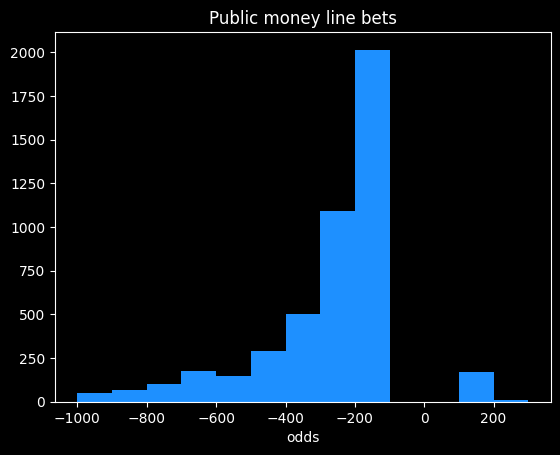

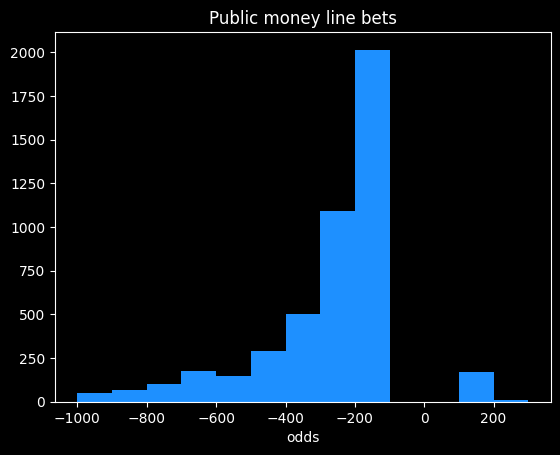

Last time, I looked at money line bets and showed that there is a bias against slight to heavy underdogs, and a possible bias against very heavy favorites. There's a lot I didn't get to, though. What kind of money line bets do the public prefer?

The public takes the home team 63% of the time, which is a little high given the home team wins 55% of games. The public also takes the money line favorite in 96% (4656/4839) of NBA games.

Is that rational or not? We know that favorites are a slightly better deal than underdogs on the money line, so in one sense it is. If someone offered you a free money line bet on the NBA, you should probably pick the favorite. The expected value is less bad than the underdog, so it's a better choice in the long run, and your chances of making some money on the bet are much higher, so it's perhaps a better choice as a single bet as well.

A gambler taking half favorites and half underdogs has a chance at winning 100% of their bets, but someone taking a highly imbalanced number of favorites (or underdogs) will have a whole lot of guaranteed losses. The gambler might correctly pick every single favorite, but close to half of their bets on favorites are still going to be losses.

Getting pigeonholed

Money lines are all at different odds, which complicates things. For this example, let's say the gambler is taking spread bets, with both sides having a roughly equal chance of winning. There are 1230 games in the season, we'll assume the favorite is a slightly better deal, so wins 51% of the time, and the gambler takes the favorite 96% of the time. Over 1230 games, the favorites go 627-603. The gambler takes 1181 favorites and 49 underdogs on the season.

The best they can possibly do on favorites is 627/1181 (53%), assuming they somehow manage to correctly bet on every single favorite that won that season. The gambler captured all of the favorites that won, so the rest of the games left over are underdog winners, meaning they'd go a perfect 49/49 in underdog games. Overall, the best they can do is (627+49)/1230, which is 54.9%. Since the break-even point is 52.4%, most of the profits are coming from the 49 underdog games.

By taking so many favorites, the pigeonhole principle means the gambler has to be perfect just to hit a 54.9% win rate. As I showed in Do you wanna win?, 54.9% is good enough to have a positive expected value on bets, but it's low enough that losing money over 1,230 bets is very possible, even with proper bankroll management. If hitting that number requires you to be perfect, it seems like a bad plan.

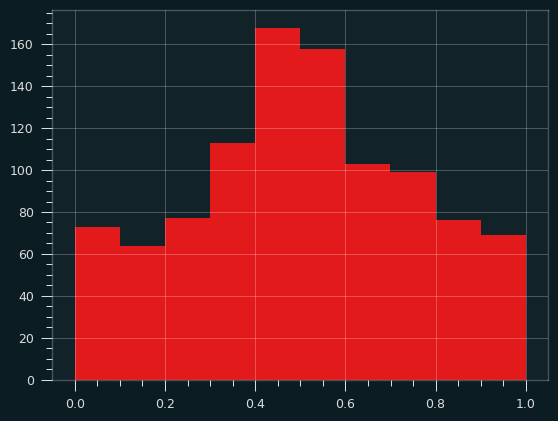

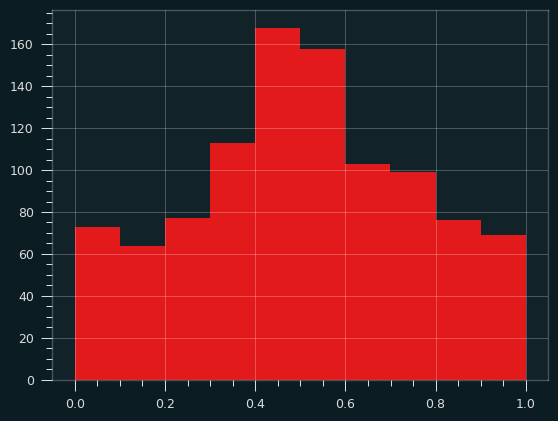

Here are the frequencies of odds taken by the public on the money line. There's an awkward gap in the middle. In the American way of writing odds, favorites are always -100 or smaller, and underdogs are always +100 or bigger.

The public mostly takes bets in the -100 to -300 range, which is in the range where money line bets have been a slightly better value than spread bets over the past four seasons, so good for them. The biggest underdog bet the public took in nearly 5,000 bets was at +400 (implying the underdog had a 20% chance of winning.)

The public achieved -2.87% rate of return on money line bets. That's bad compared to the 0% rate of return offered by not betting, but it's better than the -4.5% on spread bets, and way better than the -20% on some types of parlay bets. Someone fading, or taking the opposite bets to the public, would achieve a -6.4% rate of return.

On the rare occasions the public does take the underdog, they make a profit. On those 183 bets, the public notched a +2.43% rate of return. Bets on underdogs will have a high amount of variance, so there could be some luck involved.

Point totals

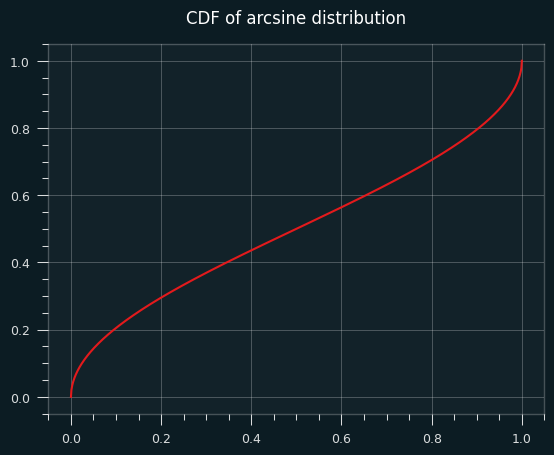

In addition to who will win the game, gamblers can wager on how many total points will be scored. For instance, if the final score is 120-115, the point total would be 235. If the line was 230, the OVER side would have won, and the UNDER lost.

The point totals are pretty balanced. The over wins 50.6% (2672/5273) of the time. However, the public takes the over 88.3% (4660/4839) of the time.

The public did a little better than a coin flip, winning 51% of over bets, and 54.5% of the 178 under bets.

I was curious whether the percent of bets on one side was correlated with higher winning percentage. If 99% of the public took the over, is that a safer bet than if only 51% of the public took it? I've broken down the public's bets on the over by quartiles:

| start % |

end % |

num games |

win % |

| 50 |

73.9 |

1165 |

50.5% |

| 73.9 |

82.4 |

1164 |

51.4% |

| 82.4 |

88.4 |

1163 |

50.9% |

| 88.4 |

100 |

1168 |

51.5% |

For 1,000 observations, a 95% confidence interval is roughly +/- \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{1000}} \approx \frac{1}{\sqrt(33*30)} \approx 3\%\), which is much bigger than the difference between 50.5% and 51.5%. So the difference isn't significant.

Are sportsbooks leaving money on the table?

It's odd to me that the over would win more than 50% of the time when that's the side that usually has the most money on it. That's not a huge imbalance, but the sportsbooks would be making more money if they increased the point totals a bit so the over loses 51% of the time instead.

Gamblers betting on point totals are probably a little more savvy than ones betting the lines. It's kind of an odd thing to bet on. Doesn't matter who won, doesn't matter whether it was a good game or not. All bets are math problems, but point totals are more obviously a math problem than money lines or spreads.

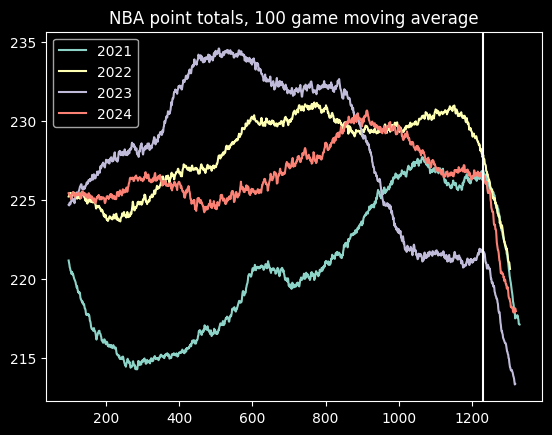

Do point totals tell us anything about the evolution of the NBA?

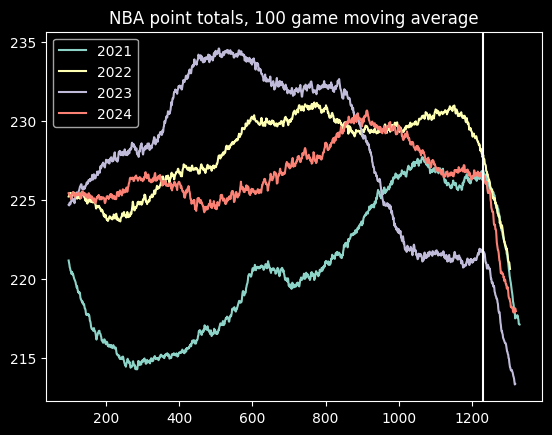

It's possible sportsbooks haven't kept up with the evolution of the game. NBA point totals have gotten much higher over the past decade due to faster pace, better shooting and more 3 pointers.

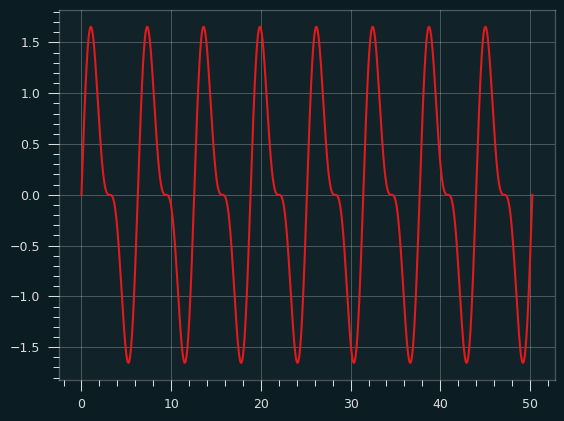

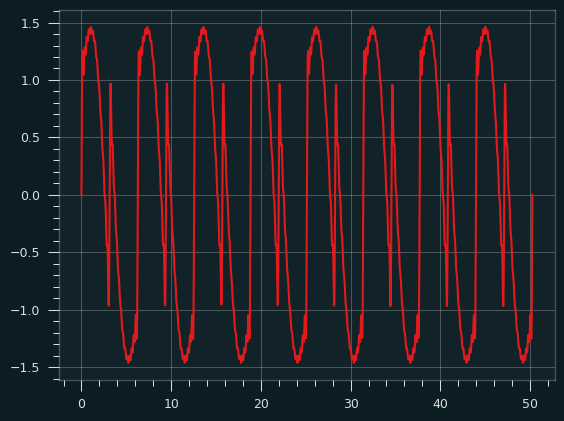

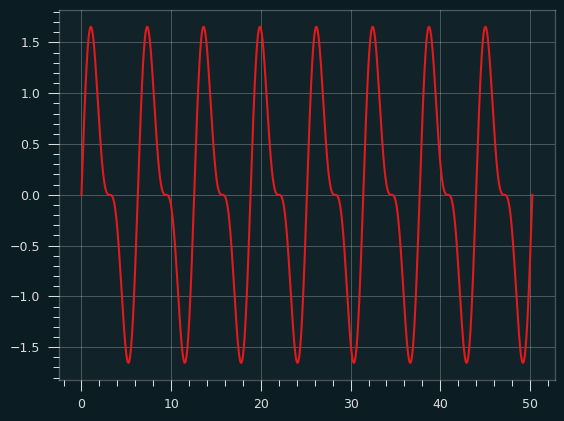

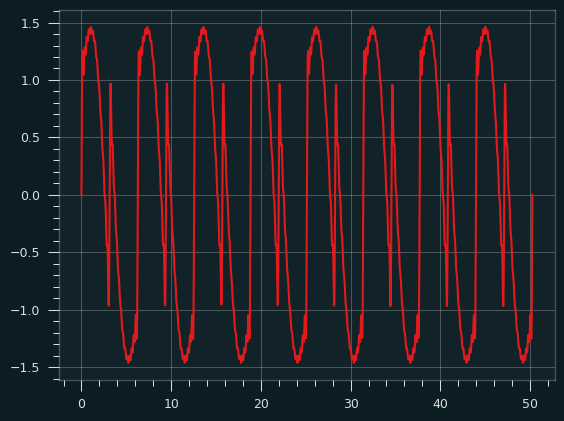

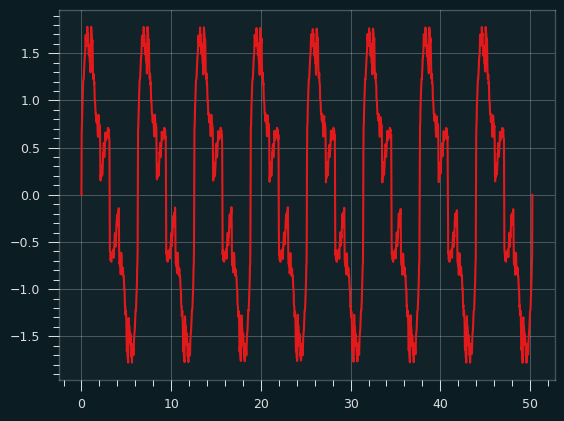

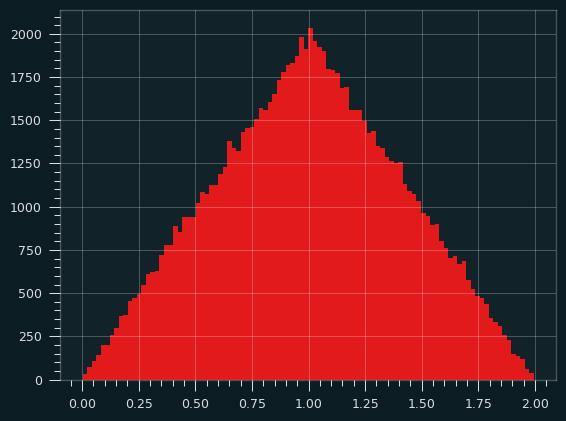

Here is a graph of moving averages of the point totals for the past four seasons:

Point totals go down at the end of every year. That's because playoff games tend to be more tightly contested than regular season games. The vertical line is where the playoffs start.

There appears to be an increase in average point totals during the 2021 season, but it's stayed fairly consistent since then, with one notable exception. There's an big dip in point totals during the 2023 season, around game 800. This is almost certainly due to a directive from the NBA telling officials to call fewer fouls. Fans (and presumably gamblers) noticed right away, but the NBA only admitted the change well after the fact. Luckily, nothing has happened since then to further undermine trust in the NBA!

Oct 19, 2025

Song: The Meters, "People Say"

In a previous installment, I looked at statistics about NBA gambling that I obtained from sportsbookreview.com. I thought it was pretty interesting, but there were some huge gaps in the data, and I wasn't sure what sportsbook some of it was coming from. So I didn't have a ton of confidence in my results.

I thought it was a pretty cool idea, though, so I tracked down a better source of data via Yahoo's NBA pages. Yahoo loads gambling data from the BetMGM sportsbook, and I found a nice internal API for getting it all. I was able to get data on the past four seasons of NBA games, and although data is missing for some games, it's much more complete, and has a bunch more info, than the original dataset.

All code and data is available online at https://github.com/csdurfee/scrape_yahoo_odds/. The explore.ipynb notebook has all the calculations and charts used in this article.

As usual with gambling content, I'm presenting this data because I think it is interesting to study how it works, and what it tells us about basketball and human nature. I don't recommend you bet based on information in this article, or at all.

The data I'm looking at is every regular season and playoff NBA game from the 2021-22, 2022-23, 2023-2024 and 2024-2025 seasons. No preseason games or All-Star games, but the Emirates NBA Cup championship game is included.

There are 435 games that are missing stake/wager data (the percentage of money and bets placed on each side, respectively.) That leaves 4,840 NBA games that I have analyzed. The stake and wager percentages seem to be pretty similar to each other, so I'm just using the wager data.

What do the spreads look like? Are there any obvious biases?

The home team went 2393-2447 (49.5%) against the spread over the last 4 years. The favorite team went 2427-2413 (50.1%) against the spread in that time.

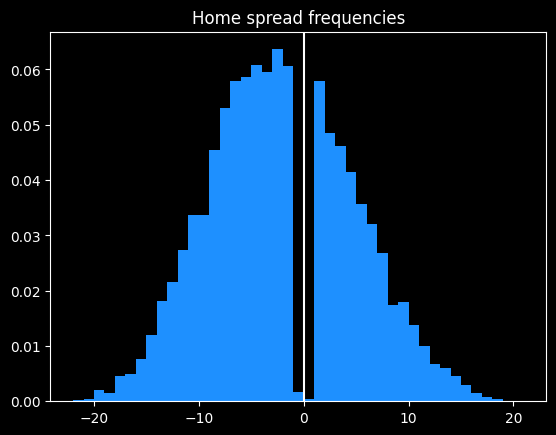

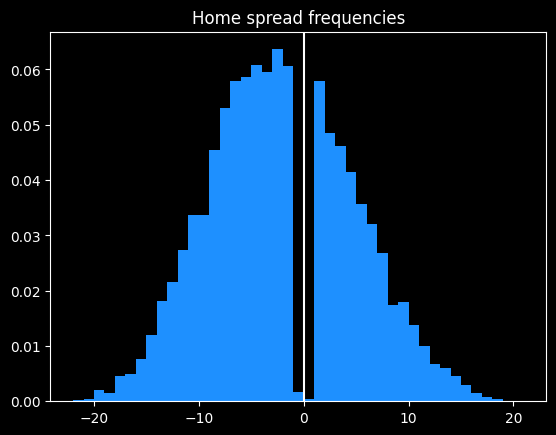

The home team was the favorite in 3044/4840 (62.8%) of games. The median spread is the home team -3.5 (favored by 3.5 points). Here are the frequencies:

Basketball games never end in a tie, and there are strategic reasons why NBA games rarely end in a one point difference.

Around half of all home lines are one of -2.5, -1.5, -4.5, -3.5, +1.5, -6.5, -5.5, -7.5 or +2.5 (in descending order of frequency).

98.3% of all MGM lines are on the half point (eg 8.5 instead of 8). This is so the sportsbook can avoid pushes (ties), where they have to give everybody's money back.

More evidence of the folly of crowds

First, some betting jargon, if you're new here. Teams that are popular with bettors are known as public teams. The side of a particular bet that gets more action is known as the public side. If that side of the bet won, people say the public won. Betting the less popular side is known as fading the public. When the less popular side wins against the spread, people will say Vegas won or sharps won (a sharp is someone who is good at betting, as opposed to a square, who is bad at betting.)

Looking at the stake/wager data, we can find out which team was more popular to bet on for each game. How do those public teams do collectively? Are the public any better or worse at making picks than just flipping a coin?

Due to well-earned cynicism, I was expecting that the public would be a bit worse than a coin flip. And they are. The public went 2381-2459 (49.19%) against the spread over the past 4 years.

The public greatly prefer betting on the away team. 2742/4840 (56.7%) of public bets are on the away team. The public also greatly prefer favorites. 2732/4840 (56.4%) of bets are on them.

Here's how the bets break down:

|

favorite |

dog |

| AWAY |

1215 |

1527 |

| HOME |

1517 |

581 |

This crosstab is a little misleading. The home team is usually favored, so there are fewer home underdogs than road underdogs. However, there's still a discrepancy. The home team is the underdog 37% of the time, but only 27% of bets on underdogs are on the home team, and 28% of bets on the home team are on underdogs.

Of the 4 categories, the only one with a winning record for the public is away favorites -- 623-592 (51.3% win rate). The second best type is home underdogs, which went 289-292 (49.7%).

The two most popular bet types with the public are big losers. Away underdogs went 742-785 (48.6%), and home favorites went a putrid 727-792 (47.9%).

Overall, someone taking the public side of every bet over the past 4 years would have lost 324 units. If they bet $100 on every game, they would be down $32,400. Someone taking the opposite side of all these bets (fading the public) would "only" lose 160 units, or $16,000.

It would've been profitable betting reduced juice (risk 106 to win 100 instead of 110) to fade the public on all away underdog and home favorite picks. The problem with that strategy is that reduced juice sportsbooks actively attract smart players, so they have sharper (more accurate) lines. A retail sportsbook like BetMGM doesn't need sharp lines because they ban any players who win too much. Against sharp lines, I wouldn't expect the strategy to be profitable.

How have teams done against the spread over the past 4 years?

Over the past 4 seasons, team records against the spread appear fairly random. The only real outlier is the Oklahoma City Thunder, who have won an astounding 59.3% of their games against the spread. This is remarkable to me because they've been one of the best and most hyped teams in basketball the past couple years. They dominated the league last season, winning 68/82 (82.9%) games, and the NBA Championship. They're not exactly an under the radar team. Yet they appear to have been underestimated by both Vegas and the betting public.

|

|

| Oklahoma City |

0.593 |

| Toronto |

0.544 |

| Boston |

0.54 |

| Memphis |

0.529 |

| Orlando |

0.528 |

| Chicago |

0.516 |

| Dallas |

0.515 |

| Cleveland |

0.508 |

| New York |

0.504 |

| Golden State |

0.504 |

| Indiana |

0.503 |

| Houston |

0.502 |

| LA Lakers |

0.5 |

| Miami |

0.499 |

| Philadelphia |

0.498 |

| Minnesota |

0.496 |

| Detroit |

0.495 |

| Utah |

0.492 |

| Denver |

0.491 |

| Sacramento |

0.49 |

| LA Clippers |

0.489 |

| San Antonio |

0.488 |

| Charlotte |

0.487 |

| Milwaukee |

0.484 |

| Brooklyn |

0.483 |

| Portland |

0.477 |

| New Orleans |

0.476 |

| Phoenix |

0.471 |

| Atlanta |

0.442 |

| Washington |

0.439 |

While it's not impossible OKC's record against the spread is due to chance alone, a 59.3% winning percentage over 332 games seems like a failure of the market.

Who are the most common favorites?

Boston has been the most dominant, being favored in 319/361 (88.4%) of their games over the past four seasons, followed by Milwaukee, Denver and Golden State.

Detroit, Charlotte, Washington and San Antonio were the most common underdogs.

|

|

| Boston |

0.884 |

| Milwaukee |

0.734 |

| Denver |

0.711 |

| Golden State |

0.707 |

| Cleveland |

0.706 |

| Phoenix |

0.691 |

| Miami |

0.608 |

| Minnesota |

0.595 |

| LA Clippers |

0.588 |

| New York |

0.572 |

| Philadelphia |

0.568 |

| Memphis |

0.56 |

| Oklahoma City |

0.557 |

| Dallas |

0.542 |

| Sacramento |

0.535 |

| LA Lakers |

0.509 |

| Atlanta |

0.498 |

| Indiana |

0.456 |

| Chicago |

0.426 |

| Toronto |

0.414 |

| Brooklyn |

0.411 |

| Utah |

0.406 |

| New Orleans |

0.385 |

| Orlando |

0.358 |

| Houston |

0.309 |

| Portland |

0.245 |

| San Antonio |

0.215 |

| Washington |

0.213 |

| Charlotte |

0.194 |

| Detroit |

0.188 |

Who are the most common public teams?

We saw the public likes to bet on the away team, and the favorite. Do they have team-specific tendencies?

They certainly do. The LA Lakers and Golden State Warriors are most popular, being the picked by the public in 72% of their games. Detroit and Orlando are the least popular, only getting the majority of bets in 31% of their games.

|

|

| LA Lakers |

0.716 |

| Golden State |

0.716 |

| Milwaukee |

0.694 |

| Phoenix |

0.607 |

| Denver |

0.603 |

| Dallas |

0.577 |

| Boston |

0.557 |

| Memphis |

0.551 |

| Chicago |

0.545 |

| Indiana |

0.541 |

| Philadelphia |

0.538 |

| Cleveland |

0.52 |

| Miami |

0.519 |

| Utah |

0.518 |

| Oklahoma City |

0.518 |

| Minnesota |

0.504 |

| LA Clippers |

0.502 |

| Brooklyn |

0.497 |

| Atlanta |

0.495 |

| New York |

0.484 |

| San Antonio |

0.436 |

| Washington |

0.425 |

| Sacramento |

0.417 |

| Houston |

0.401 |

| Toronto |

0.382 |

| Charlotte |

0.359 |

| Portland |

0.341 |

| New Orleans |

0.322 |

| Detroit |

0.314 |

| Orlando |

0.311 |

This is a very similar ranking to what I saw in the previous data -- the public don't appear to be picking bets for purely rational reasons. They like to bet on popular teams, good teams, and teams with popular players. They don't like to bet on unpopular or bad teams, even though both sides have the same chance of winning against the spread. It makes sense as an aesthetic choice, but not as a mathematical choice.

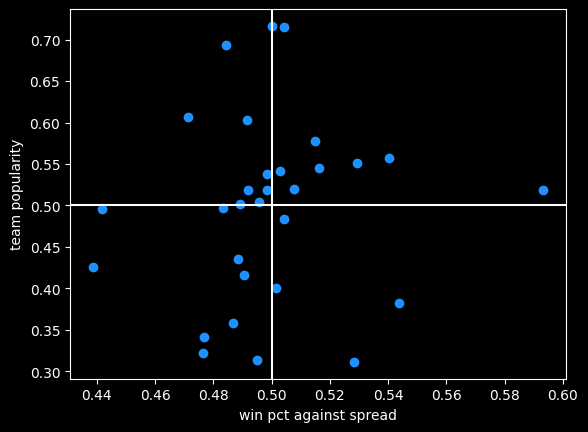

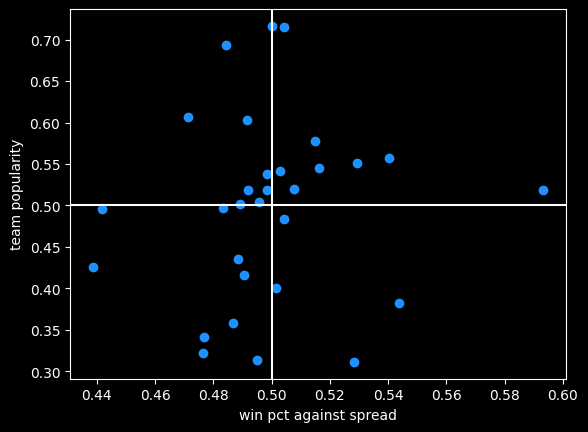

There is a bit of correlation (r = .08) between team popularity and their record against the spread. Bettors do slightly prefer to bet on teams that do well against the spread:

Oklahoma City is that lonely dot far off to the right, far better than every other team but only slightly more popular than average.

Money lines and the favorite/longshot bias

So far I've only been looking at bets against the spread. This new dataset also includes info on money line bets.

In some ways, money line bets are easier to understand -- just bet on the team you think will win. If you like the favorite, you will win less than you risk; if you like the underdog you win more than you risk. If it's say Oklahoma City versus Dallas, the two sides might be OKC -320 (risk $320 to win $100, implying about a 75% chance of winning) and DAL +260 (risk $100 to win $260).

With spread bets, both sides have an equal chance of winning, and are usually priced the same. But with money lines, the gambler doesn't know the true odds, so they don't know the vig they're paying.

There is data to suggest that underdogs pay more in vig, and are therefore more profitable for the sportsbook. This is called the favorite-longshot bias -- conventional betting wisdom is the expected value of taking an underdog money line bet (especially a big underdog) is lower than taking the favorite. People who bet the underdog are in essence paying a premium to have a more thrilling outcome if they do win.

While it's a documented phenomenon in horse racing, there's some debate as to whether it exists in general, so I analyzed the 4,634 games with money line betting data.

If somebody always bet the favorite on every NBA game, or the underdog, what would be their rate of return? Is it better or worse than the -4.5% rate on spread bets?

I did find evidence of the favorite-longshot bias in the NBA money lines. When risking a constant amount of money on each bet, underdogs had a rate of return of -5.47% versus -4.09% for favorites. Favorites between -200 and -400 offer the best rate of return of any type of money line bet, at -2.97%. Every single type of underdog bet does worse than -4.5% of the typical spread bet.

| label |

start |

end |

num games |

return % |

| all faves |

-9999 |

-1 |

4839 |

-4.09% |

| mild faves |

-200 |

-1 |

2174 |

-4.19% |

| heavy faves |

-400 |

-200 |

1612 |

-2.97% |

| huge faves |

-9999 |

-400 |

1053 |

-5.59% |

| all dogs |

1 |

9999 |

4634 |

-5.47% |

| mild dogs |

1 |

200 |

2440 |

-5.60% |

| heavy dogs |

200 |

400 |

1430 |

-5.69% |

| huge dogs |

400 |

9999 |

764 |

-4.65% |

The number of dogs and favorites aren't equal because some games have money lines where both sides are negative, say -110, like a traditional bet with a spread of zero. There's also a big asymmetry when the odds are long. For instance the favorite might be -800 and the underdog is +561. That doesn't represent a huge vig, it's just a quirk of how American-style odds work (covered in the book).

Caveats and bootstraps

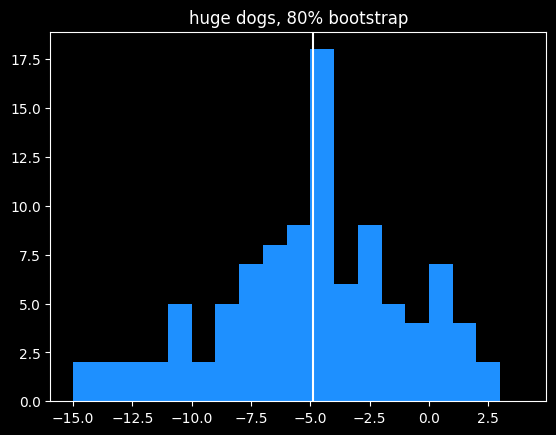

The table above isn't telling the whole story. I'm not conveying a sense of the volatility in the rate of return. Huge underdogs have a bigger payout when they do win, so the outcomes are going to be a lot more variable than betting the favorites.

-4.65% is the best estimate of the rate of return for huge underdogs, but maybe we just got lucky, or unlucky. A couple of longshot bets winning or losing could drastically change the overall return rate.

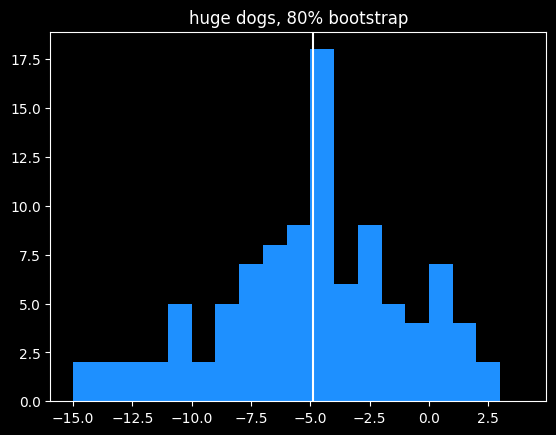

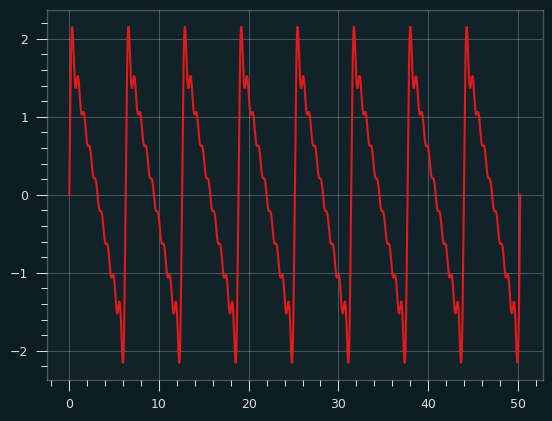

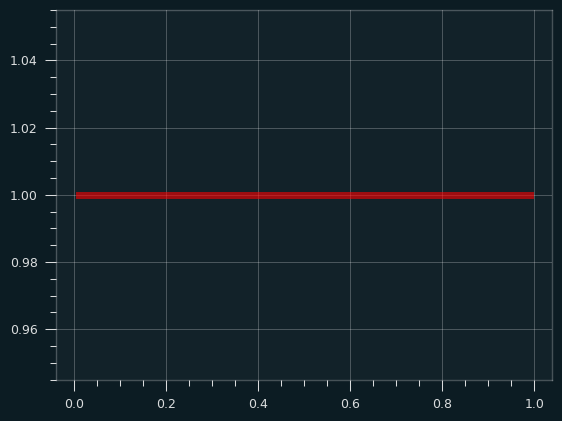

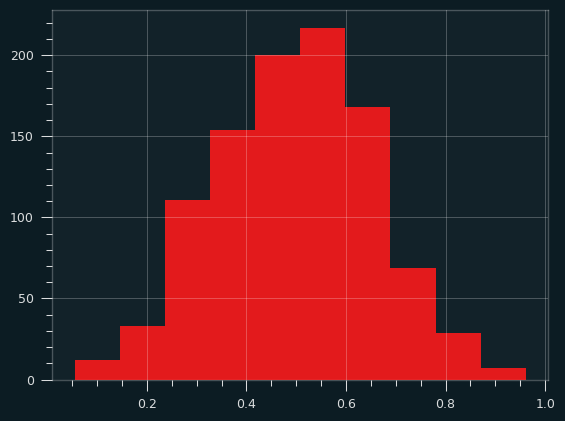

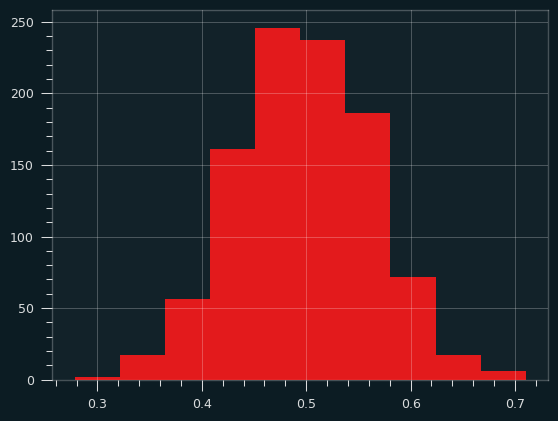

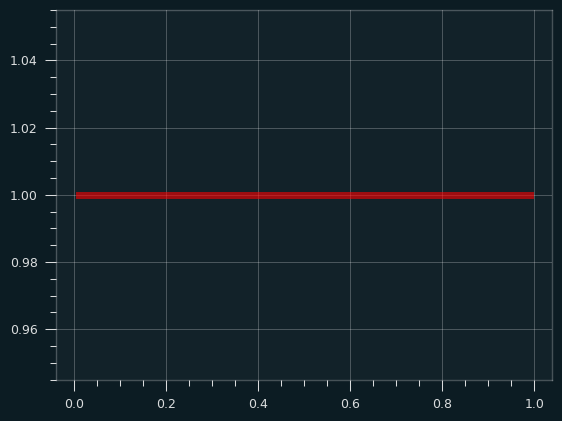

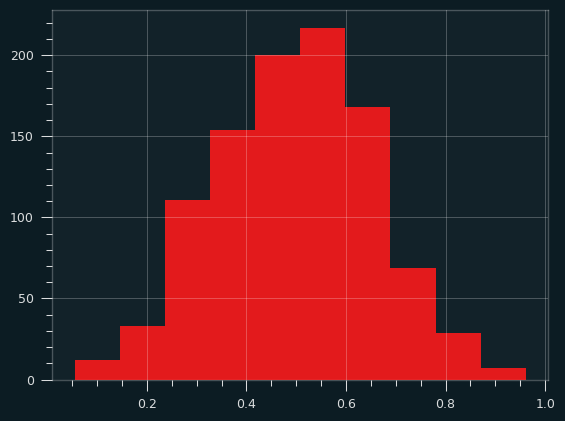

To test volatility, I used bootstrapping, previously covered in one in e. I repeatedly randomly sampled 80% (611/764) of the huge underdog bets and calculated the rate of return on that set. Looking at the range of outcomes helps illustrate the variability of these bets.

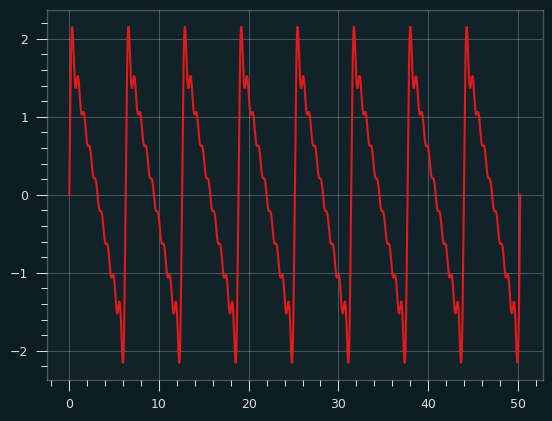

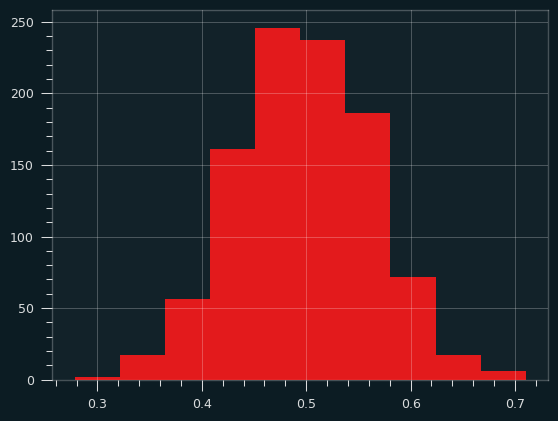

Doing that 100 times leads to a pretty wide spread of rates of return:

Although the mean value is close to the overall mean, 15% of bootstrapped samples actually had a positive rate of return. This is similar to what we saw in cool parlay, bro, where due to variance, even gamblers with no advantage over the house had a small chance of making money over a long period of time off of parlays. I described that situation "like a lottery where you have a 12% chance of winning $3,617, but an 88% chance of losing $10,221." This is a similar proposition.

Bridgejumper parlays and p-hacking

We'd need a lot more data to get a crisp estimate of the rate of return on huge underdogs, but we can have more confidence in the estimated -5.59% rate for huge favorites. Huge favorites being disadvantaged kind of contradicts the favorite-longshot bias theory, but it doesn't surprise me at all due to a strange phenomenon I've seen over and over again online.

It's a type of bet sharps might call "bridgejumper parlays" and squares on the internet unironically call "free money parlays" -- a parlay of a whole bunch of heavy favorite money lines together.

The gambler starts with some heavy favorite they like and keep adding more heavy favorites to the parlay till they get plus odds (they can win more than they risk), ending up with 5-6 heavy favorites on the same parlay. They will pick legs of the parlay from different sports, if necessary. There usually aren't enough heavy favorites in the NBA on a particular night to get to the magic > +100 payout.

An example you might see posted on reddit or twitter would be a 6 leg parlay with a payout of +105 like:

- Celtics -600

- Nuggets -900

- OKC -1000

- Lakers -600

- Duke -600

- Some UFC Guy, because they needed a sixth bet -700

I've talked to a couple people who take bridgejumper parlays, and they genuinely seem to think they've found some kind of glitch in the matrix -- all of the legs of the bet have a high chance of winning, therefore the bet is a sure thing.

A sensible person would know that sportsbooks aren't in the business of offering free money so maybe they're missing something. A humble person would assume they probably hadn't discovered some clever trick the sportsbooks don't know about. But most people who get into betting aren't sensible or humble (they think they can see the future, after all), so for a certain class of bettor, this type of wager just feels like a sure thing.

In parlay form, the fallacy seems obvious to me. Just because the individual risk on each leg of the parlay is small, that doesn't mean the combined risk is.

There's a more sophisticated version of this fallacy in statistics called p-hacking. As always, there's an xkcd about it. A particular experiment might have a 5% chance of giving a false result. 5% is a pretty small number. But if you do 13 of those experiments, there's about a 50% chance that at least one of them will give a false result. Even people who are good at math and science probably don't have a good sense of what \(.95^{13}\) equals. It's sort of like a 13 leg parlay of money line bets at -1900.

Next time: more on point totals, money lines, and human nature.

Sep 23, 2025

Song: John Hollenbeck & NDR Big Band, "Entitlement"

I've been messing around with prime numbers, because there are several places where they intersect with both random walks and the arcsine distribution. It's going to take a while to finally tie that bow, though.

So it's a quick one this week: a kinda-cool story, and a kinda-cool graph.

Random Primes

The prime numbers are simple to find, but not easy. They're not randomly distributed, but it's hard to come up with easy ways to find them, and they act like random numbers in certain ways. Why is 47 prime and 57 non-prime? You can't really tell just by looking.

To find the primes, we can write down every number from, say, 1 to 1000. Then we cross out 2, and every number divisible by 2 (4, 6, 8, etc.). Repeat that with 3 (6, 9, 12, etc.), and so on. The numbers left behind are prime. This is the famous Sieve of Eratosthenes -- it's a tedious way to find prime numbers, but it's by far the easiest to understand.

The sieve gave mathematician David Hawkins an idea [1]: what about doing that same process, but randomly? For each number, flip a coin, if it comes up heads, cross the number out. That will eliminate half of the numbers on the first pass. Take the lowest number k that remains and eliminate each of the remaining numbers with probability 1/k. Say it's 4. For each remaining number, we flip a 4 sided die and if it comes up 4, we cross it out.

If we go through all the numbers, what's left over won't look like real prime numbers -- there should be as many even fake primes as odd ones, for starters. But the remaining numbers will be as sparse as the actual prime numbers. As the sample size N heads to infinity, the chances of a random number being a real prime, and being a fake prime, are the same -- 1/log(N).

This is a brilliant way to figure out what we know about prime numbers are due to their density, and what are due to other, seemingly more magical (but still non-random) factors.

Several characteristics of real primes apply to the random primes. And tantalizingly, things that can't be proven about real primes can be proven about the fake ones. It's been conjectured that there are infinitely many pairs of twin primes -- primes that are separated by 2 numbers. An example would be 5 and 7, or 11 and 13. It makes sense for a lot of reasons that there should be an infinite number of twin primes. But mathematicians have been trying to prove it for over 150 years, without success.

Random primes can be odd or even, so the analogy to twin primes would be two random primes that are only one apart, say 5 and 6. It's relatively simple to prove that there are an infinite number of random twin primes [2]. That could easily be fool's gold -- treating the primes like they're randomly distributed gives mathematicians a whole toolbox of statistical techniques to use on them, but they're not random, or arbitrary. They're perfectly logical, and yet still inscrutible, hidden in plain sight.

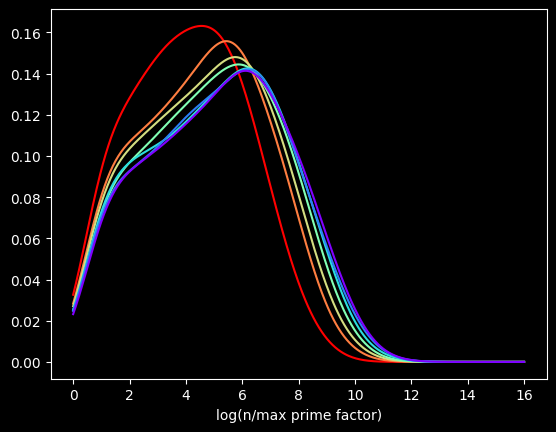

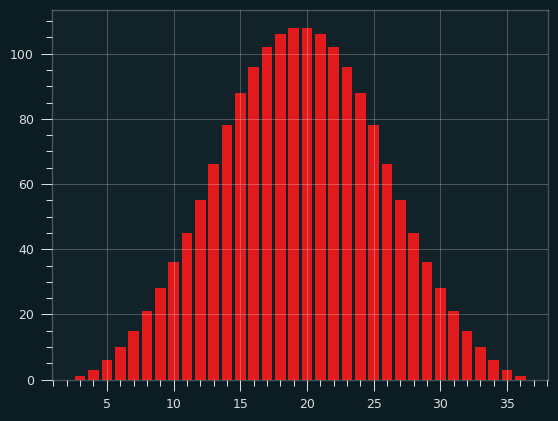

Largest prime factors of composite numbers

I was intrigued by the largest prime factor of composite (non-prime) numbers. Are there any patterns?

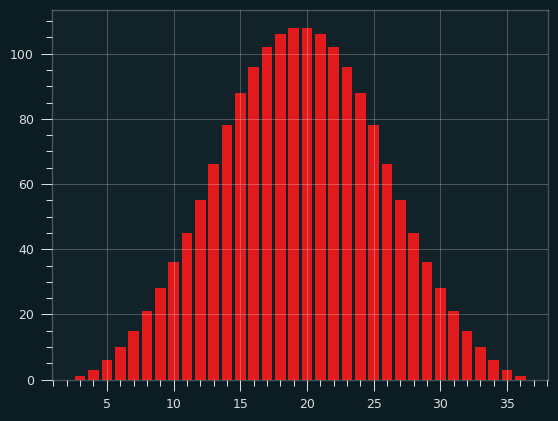

As background, every number can be split into a unique set of prime factors. For instance, the number 24 can be factored into 24 = 8 * 3 = 2 * 2 * 2 * 3. Let's say we knock off the biggest prime factor. We get: 2 * 2 * 2 = 8. The raw numbers rapidly get too big, so I looked at the log of the ratio:

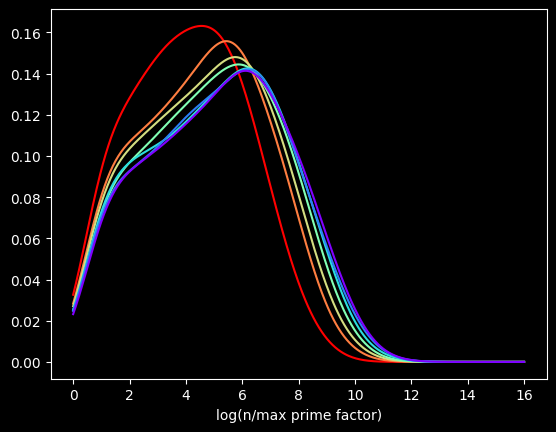

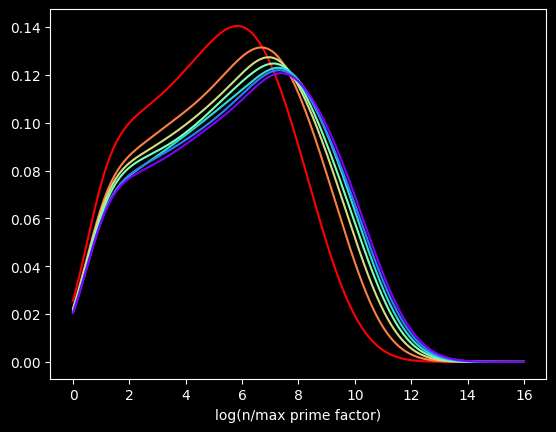

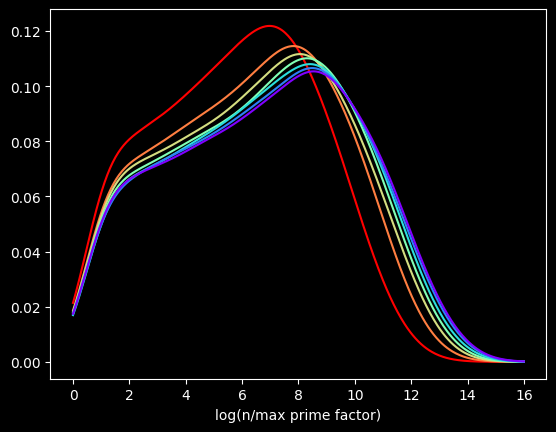

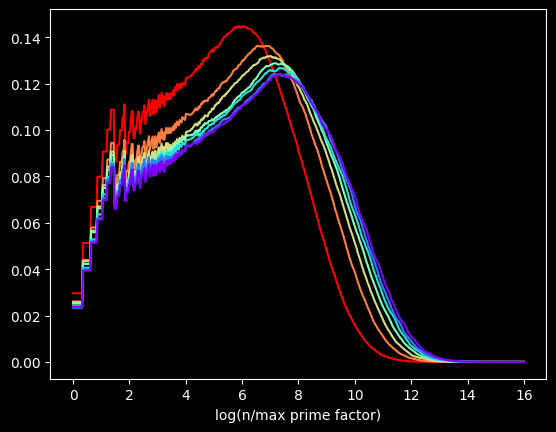

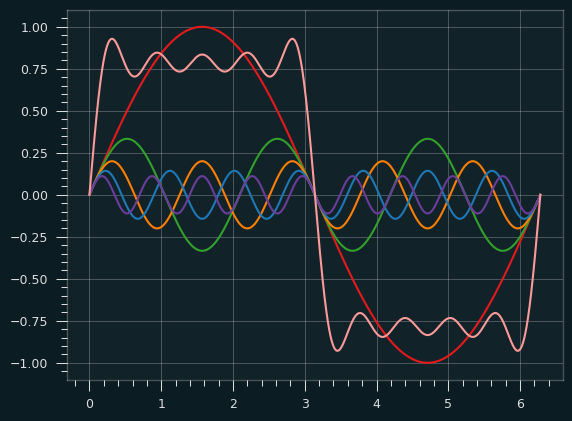

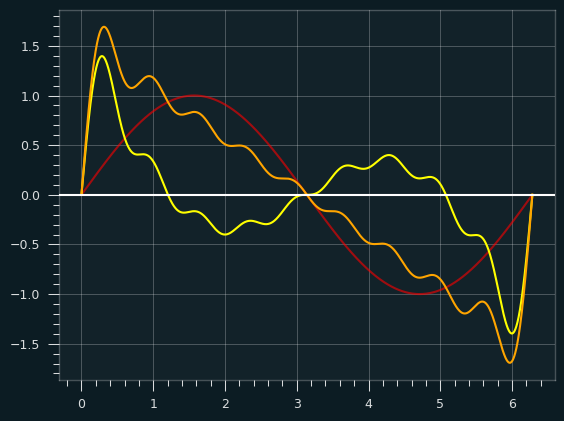

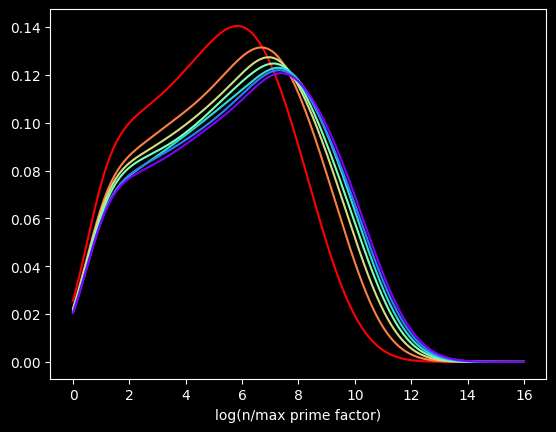

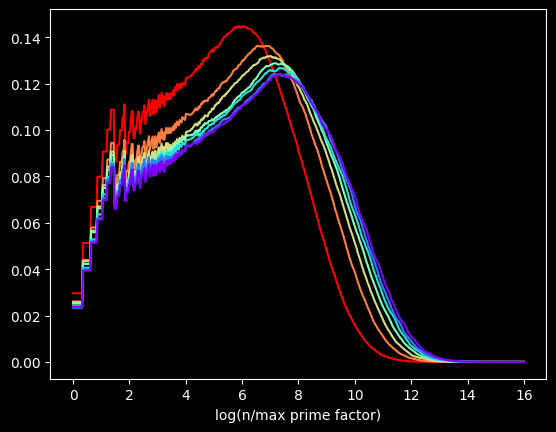

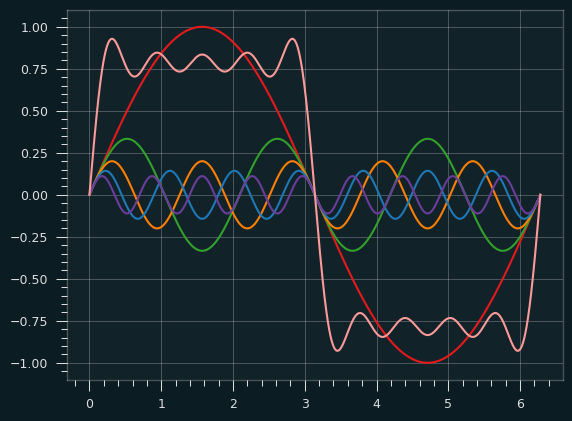

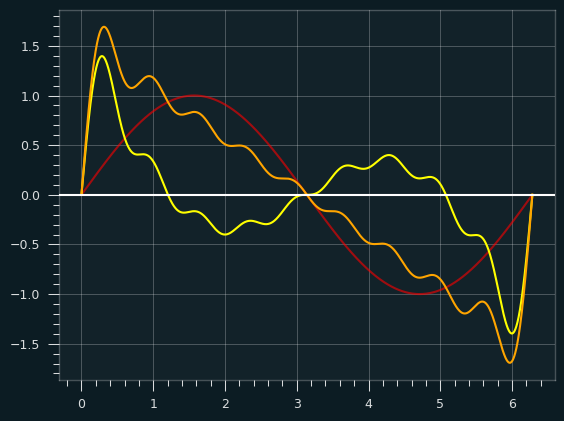

The red curve is the distribution of the first 100,000 composite numbers, the orange is the next 100,000 composite numbers, and so on.

What if we bump up an order of magnitude? This time, the red curve is the first million composite numbers, the orange is the next million, and so on. Here's what that looks like:

Pretty much the same graph, right? The X axis is different, but the shapes are very similar to the first one.

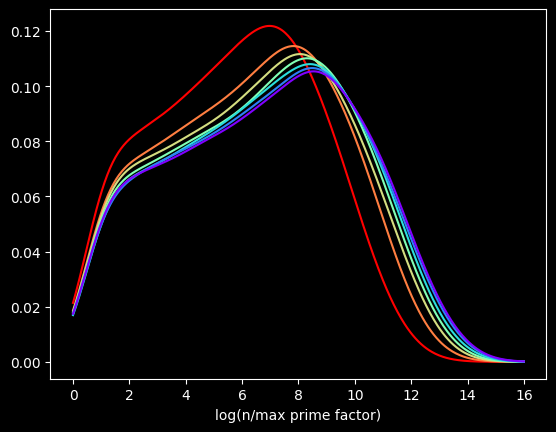

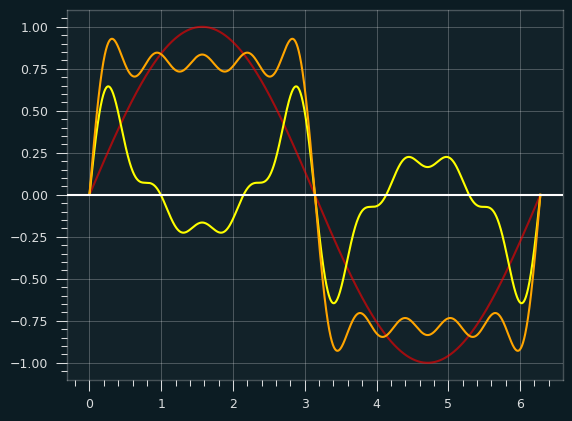

Let's go another order of magnitude up. The first 10,000,000 versus the next 10,000,000, and so on?

We get the same basic shapes again! The self-similarity is kinda cool. Is it possible to come up with some function for the distribution for this quantity? You tell me.

The perils of interpolation

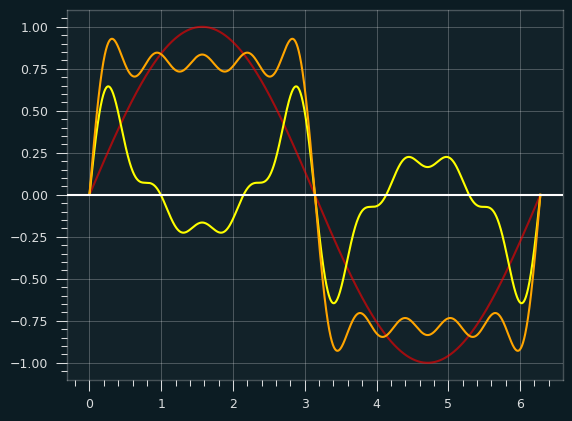

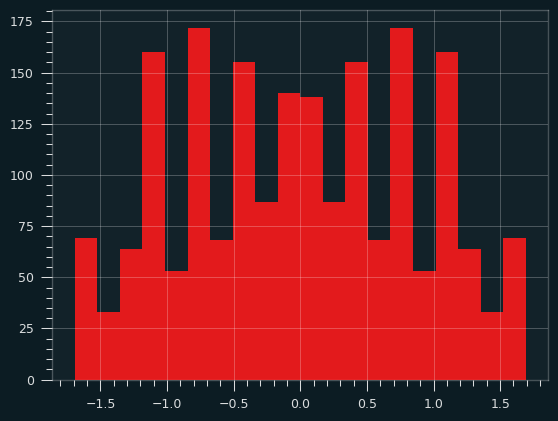

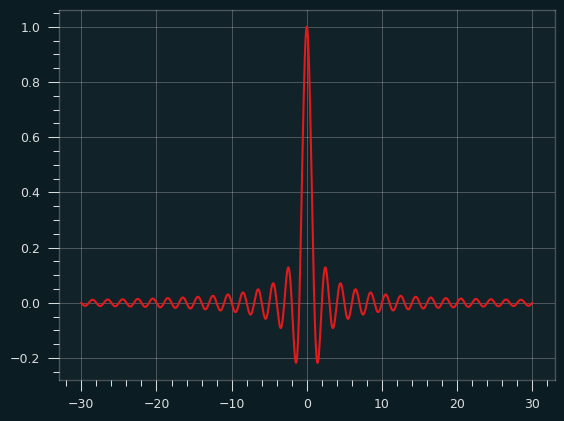

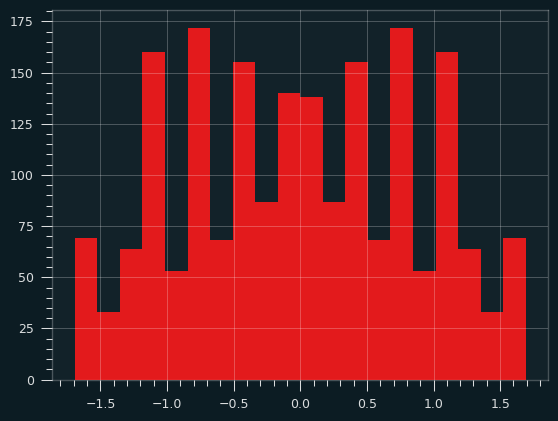

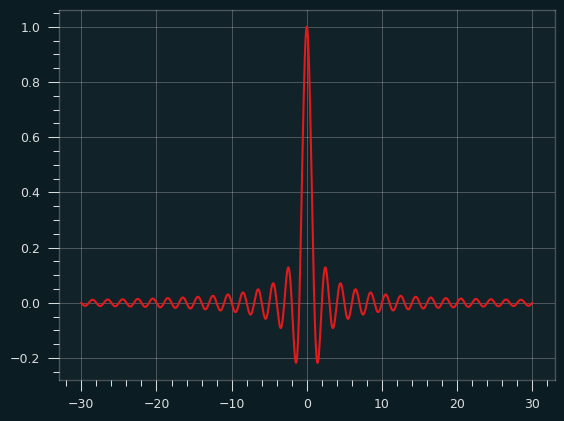

These graphs are flawed. I'm generating these graphs using Kernel Density Estimation, a technique for visualizing the density of data. Histograms, another common way, can be misleading. The choice of bin size can radically alter what the histogram looks like.

But KDE can also be misleading. These graphs make it look like the curve starts at zero. That's not true. The minimum possible value happens when a number is of the form 2*p, where p is a prime -- the value will be log(2), about .693.

This data is actually way chunkier than KDE is treating it. Every point of data is the log of a whole number. So there aren't that many unique values. For instance, between 0 and 1 on the X axis, there's only one possible value -- log(2). Between 1 and 3, there are only 18 possible values, log(2) thru log(19) -- those being the only integers with a log less than 3 and greater than 1.

This makes it hard to visualize the data accurately. There are too many possible values to display each one individually, but not enough for KDE's smoothing to be appropriate.

The kernel in Kernel Density Estimation is the algorithm used to smooth the data -- it's basically a moving average that assumes something about the distribution of the data. People usually use the Gaussian kernel, which treats the data like a normal distribution -- smooth and bell curvy. A better choice for chunky data is the tophat kernel, which treats the space between points like a uniform distribution -- in other words, a flat line. If the sparseness of the data on the X axis were due to a small sample size, the tophat kernel would display plateaus that aren't in the real data. But here, I calculated data for the first 100 Million numbers, so there's no lack of data. The sparseness of the data is by construction. log(2) will be the only value between 0 and 1, no matter how many numbers we go up to. So the left side of the graph should look fairly chunky.

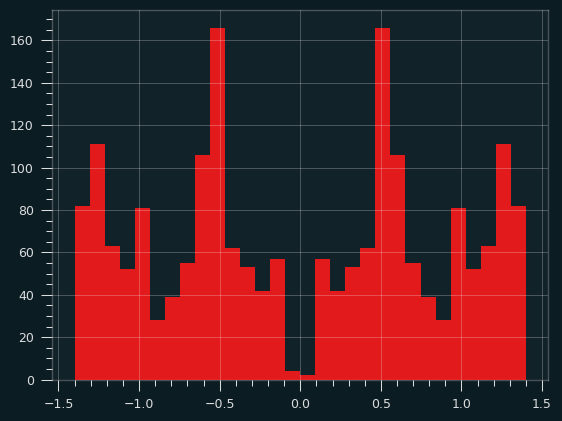

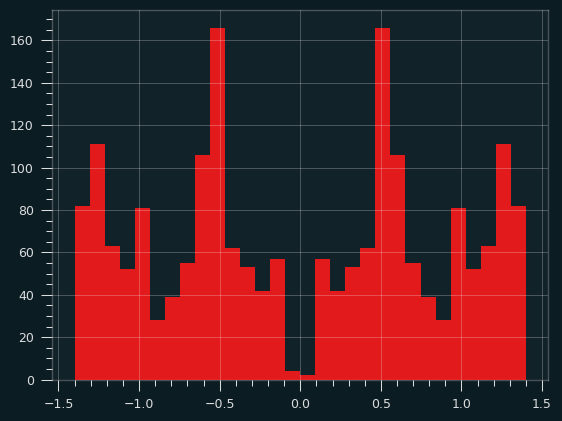

The tophat kernel does a much better job of conveying the non-smoothness of the distribution:

References

[1] https://chance.dartmouth.edu/chance_news/recent_news/chance_primes_chapter2.html

[2] for sufficiently large values of simple

[3] https://scikit-learn.org/stable/auto_examples/neighbors/plot_kde_1d.html

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernel_density_estimation

Sep 10, 2025

Song: Klonhertz, "Three Girl Rhumba"

Notebook available here

Think of a number

Pick a number between 1-100.

Say I write down the numbers from 1-100 on pieces of paper and put them in a big bag, and randomly select from them. After every selection, I put the paper back in the bag, so the same number can get picked more than once. If I do that 100 times, what is the chance of your number being chosen?

The math isn't too tricky. It's often easier to calculate the chances of a thing not happening, then subtract that from 1, to get the chances of the thing happening. There's a 99/100 chance your number doesn't get picked each time. So the probability of never getting selected is \((99/100)^{100} = .366\). Subtract that from one, and there's a 63.4% chance your number will be chosen. Alternately, we'd expect to get 634 unique numbers in 1000 selections.

When I start picking numbers, there's a low chance of getting a duplicate, but that increases as I go along. On my second pick, there's only a 1/100 chance of getting a duplicate. But if I'm near the end and have gotten 60 uniques so far, there's a 60/100 chance.

It's kind of a self-correcting process. Every time I pick a unique number, it increases the odds of getting a duplicate on the next pick. Each pick is independent, but the likelihood of getting a duplicate is not.

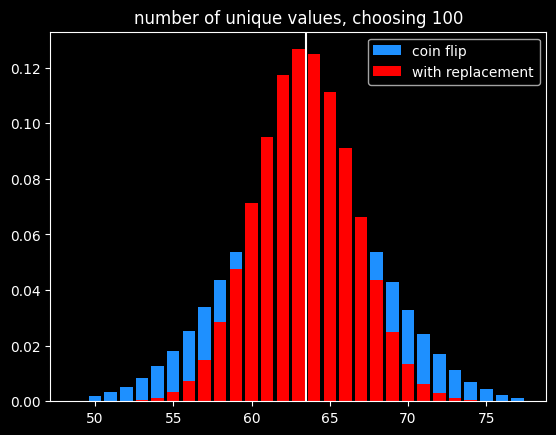

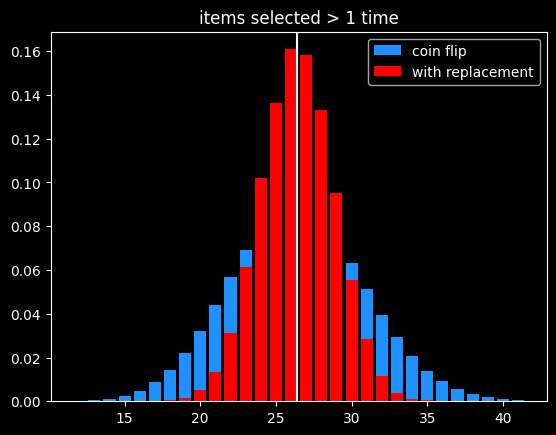

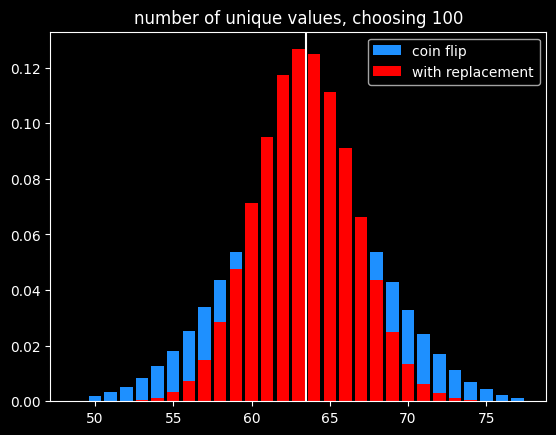

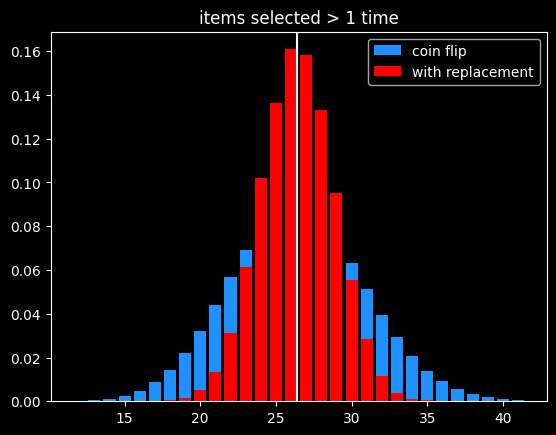

I could choose the numbers by flipping a biased coin that comes up heads 63.4% of the time for each one instead. I will get the same number of values on average, and they will be randomly chosen, but the count of values will be much more variable:

Of course, if the goal is to select exactly 63 items out of 100, the best way would be to randomly select 63 without replacement so there is no variation in the number of items selected.

A number's a number

Instead of selecting 100 times from 100 numbers, what if we selected a bajillion times from a bajillion numbers? To put it in math terms, what is \(\lim\limits_{n\to\infty} (\frac{n-1}{n})^{n}\) ?

It turns out this is equal to \(\frac{1}{e}\) ! Yeah, e! Your old buddy from calculus class. You know, the \(e^{i\pi}\) guy?

As n goes to infinity, the probability of a number being selected is \(1-\frac{1}{e} = .632\). This leads to a technique called bootstrapping, or ".632 selection" in machine learning (back to that in a minute).

Don't think of an answer

What are the chances that a number gets selected exactly once? Turns out, it's \(\frac{1}{e}\), same as the chances of not getting selected! This was surprising enough to me to bother to work out the proof, given at the end.

That means the chances of a number getting selected more than once is \(1 - \frac{2}{e}\).

The breakdown:

- 1/e (36.8%) of numbers don't get selected

- 1/e (36.8%) get selected exactly once

- 1-2/e (26.4%) get selected 2+ times

As before, the variance in number of items picked 2+ times is much lower than flipping a coin that comes up heads 26.4% of the time:

Derangements

Say I'm handing out coats randomly after a party. What are the chances that nobody gets their own coat back?

This is called a derangement, and the probability is also 1/e. An almost correct way to think about this is the chance of each person not getting their own coat (or each coat not getting their own person, depending on your perspective) is \(\frac{(x-1)}{x}\) and there are \(x\) coats, so the chances of a derangement are \(\frac{x-1}{x}^{x}\).

This is wrong because each round isn't independent. In the first case, we were doing selection with replacement, so a number being picked one round doesn't affect its probability of being picked next round. That's not the case here. Say we've got the numbers 1 thru 4. To make a derangement, the first selection can be 2, 3 or 4. The second selection can be 1, 3 or 4. But 3 or 4 might have been picked in the first selection and can't be chosen again. 2/3rds of the time, there will only be two options for the second selection, not three.

The long way 'round the mountain involves introducing a new mathematical function called the subfactorial, denoted as \(!x\), which is equal to the integer closest to \(\frac{x!}{e}\). \(e\) gets in there because in the course of counting the number of possible derangements, a series is produced that converges to \(1/e\).

The number of derangements for a set of size x is \(!x\) and the number of permutations is \(x!\), so the probability of a derangement as x gets big is \(\frac{!x}{x!} = \frac{1}{e}\)

What about the chances of only one person getting their coat back? It's also \(\frac{1}{e}\), just like the chances of a number getting selected exactly once when drawing numbers with replacement. The number of fixed points -- number of people who get their own coat back -- follows a Poisson distribution with mean 1.

The second process seems very different from the first one. It is selection with replacement versus without replacement. But \(e\) is sort of the horizon line of mathematics -- a lot of things tend towards it (or its inverse) in the distance.

Bootstrapping

Say we're working on a typical statistics/machine learning problem. We're given some training data where we already know the right answer, and we're trying to predict for future results. There are a ton of ways we could build a model. Which model will do the best on the unknown data, and how variable might the accuracy be?

Bootstrapping is a way to answer those questions. A good way to estimate how accurate a model will be in the future is to train it over and over with different random subsets of the training data, and see how accurate the model is on the data that was held out. That will give a range of accuracy scores which can be used to estimate how well the model will be on new inputs, where we don't know the answers ahead of time. If the model we're building has a small set of parameters we're fitting (like the coefficients in a linear regression), we can also estimate a range of plausible values for those parameters. If that range is really wide, it indicates a certain parameter isn't that important to the model, because it doesn't matter if it's big or small.

Bootstrapping is a way of answering those questions, using the process described before -- if we have x datapoints, pick x numbers without replacement x times. The ones that get selected at least once are used to train the models, and the ones that don't get selected are used to generate an estimate of accuracy on unseen data. We can do that over and over again and get different splits every time.

It's a fine way to split up the training data and the validation data to generate a range of plausible accuracy scores, but I couldn't find a good reason other than tradition for doing it that way. The 63.2/36.8 split isn't some magical value. Instead of having the numbers that weren't picked be the holdout group, we could instead leave out the numbers that were only picked once (also 1/e of the numbers), and train on the ones not selected or selected more than once. But picking 63% of values (or some other percentage) without replacement is the best way to do it, in my opinion.

The original paper doesn't give any statistical insight into why the choice was made, but a remark at the end says, "it is remarkably easy to implement on the computer", and notes the $4 cost of running the experiments on Stanford's IBM 370/168 mainframe. Maybe it's just the engineer in me, but it seems like a goofy way to do things, unless you actually want a variable number of items selected each run.

In the notebook, I showed that bootstrapping is about 40% slower than selection without replacement when using numpy's choice() function. However, the cost of selecting which items to use for training vs. testing should be insignificant compared to the cost of actually training the models using that train/test split.

A chance encounter

A quick proof of the chances of being selected exactly once.

Doing x selections with replacement, the chance of a number being chosen as the very first selection (and no other times) is

\(\frac{1}{x} * \frac{x-1}{x}^{x-1}\)

There are x possible positions for a number to be selected exactly once. Multiply the above by x, which cancels out 1/x. So the chances of a number being selected exactly once at any position is \((\frac{x-1}{x})^{x-1}\).

Let's try to find a number \(q\) so that \(\lim\limits_{x\to\infty} (\frac{x-1}{x})^{x-1} = e^{q}\).

Taking the log of both sides:

\(q = \lim\limits_{x\to\infty} (x-1) * log(\frac{x-1}{x}) = \lim\limits_{x\to\infty} \frac{log(\frac{x-1}{x})}{1/(x-1)}\)

Let

\(f(x) = log(\frac{x-1}{x})\)

and

\(g(x) = \frac{1}{x-1}\)

By L'Hopital's rule, \(\lim\limits_{x\to\infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim\limits_{x\to\infty}\frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}\)

The derivative of a log of a function is the derivative of the function divided by the function itself, so:

\(f'(x) = \frac{d}{dx} log(\frac{x-1}{x}) = \frac{d}{dx} log(1 - \frac{1}{x}) = \frac{\frac{d}{dx}(1-\frac{1}{x})}{1-\frac{1}{x}} =\frac{\frac{1}{x^{2}}}{{1-\frac{1}{x}}} = \frac{1}{x^{2}-x} = \frac{1}{x(x-1)}\)

and

\(g'(x) = \frac{-1}{(x-1)^{2}}\)

Canceling out (x-1) from both, \(\frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)} = \frac{1}{x} * \frac{x-1}{-1} = -1 * \frac{x-1}{x}\).

So \(q = \lim\limits_{x\to\infty} -1 * \frac{x-1}{x} = -1\)

At the limit, the probability of being selected exactly once is \(e^{-1} = \frac{1}{e}\)

References/Further Reading

https://oeis.org/A068985

https://mathworld.wolfram.com/Derangement.html

Great explanation of how to calculate derangements using the inclusion-exclusion principle: https://www.themathdoctors.org/derangements-how-often-is-everything-wrong/

The bible of machine learning introduces bootstrapping, but no talk of why that selection process. https://trevorhastie.github.io/ISLR/ISLR%20Seventh%20Printing.pdf

The original bootstrap paper: https://sites.stat.washington.edu/courses/stat527/s14/readings/ann_stat1979.pdf

Aug 08, 2025

Song: The Impressions, "Do You Wanna Win?"

(This is an excerpt from a larger project about sports gambling. Code used, and early drafts of some of the chapters can be found at https://github.com/csdurfee/book.)

I'm going to return to the subject of sports betting this week. Let's start with something easy. How do you avoid going broke betting on sports? That's easy. Reduce your bet size to zero. Scared money don't lose none.

As long as there is randomness, there will be outliers and unexpected results. It is impossible to escape randomness in sports betting. Any time you decide to bet, you enter the kingdom of randomness and have to abide by its laws. It doesn't matter whether you have an advantage over the house (unless the advantage is truly massive). Nothing is guaranteed.

This is a pretty hard thing for us to know how to deal with, when our brains are pattern-finding machines. Our brains will find patterns to give us a sense of control.

Notes

I talk about "win rate" a bunch below. That means the percent of the time a gambler can win bets at even odds (such as a standard spread bet on the NBA or NFL.)

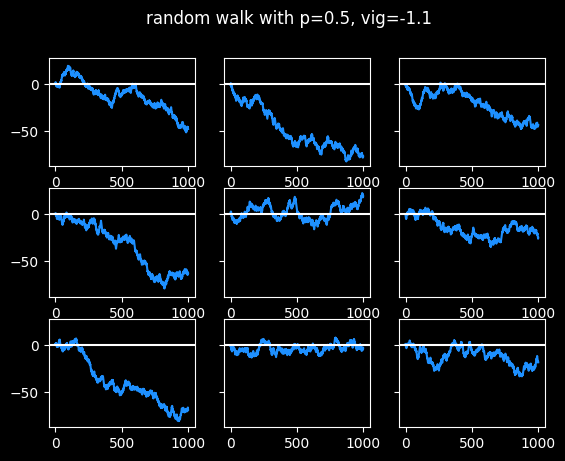

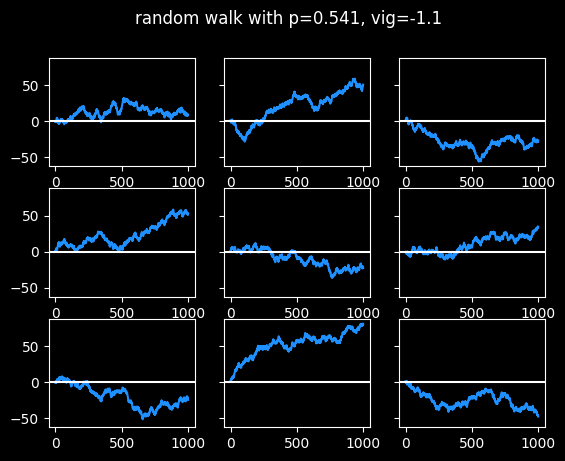

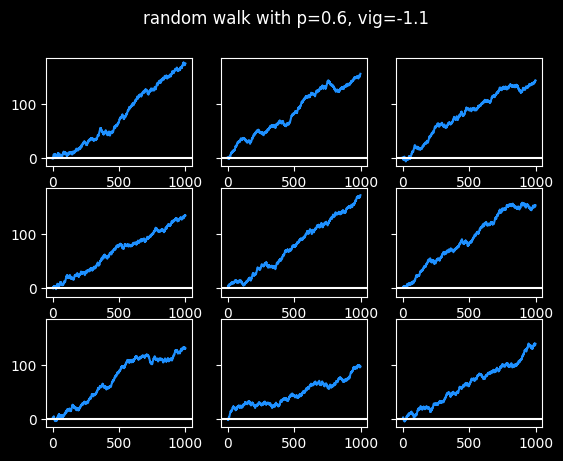

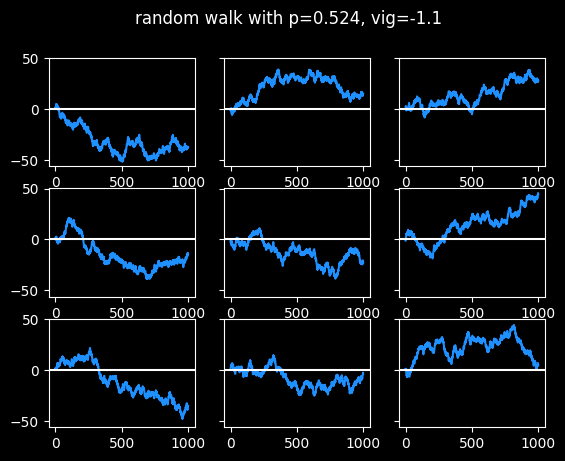

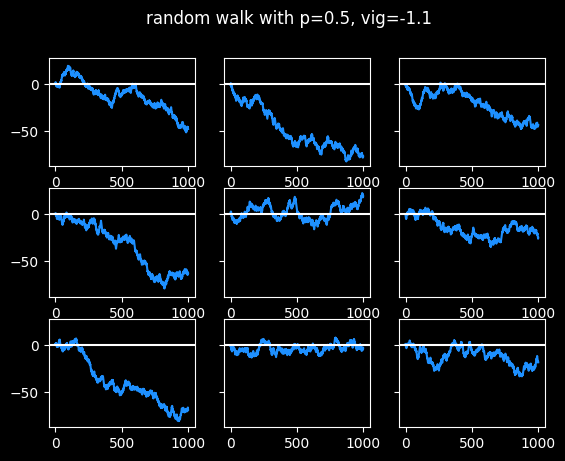

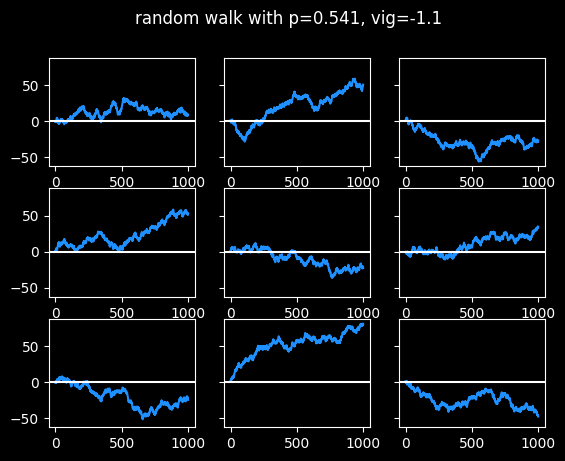

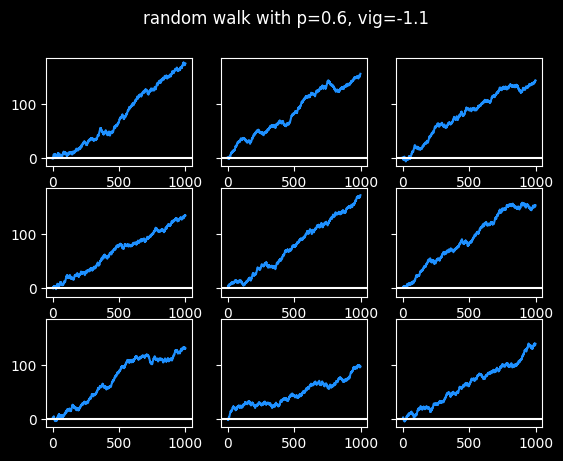

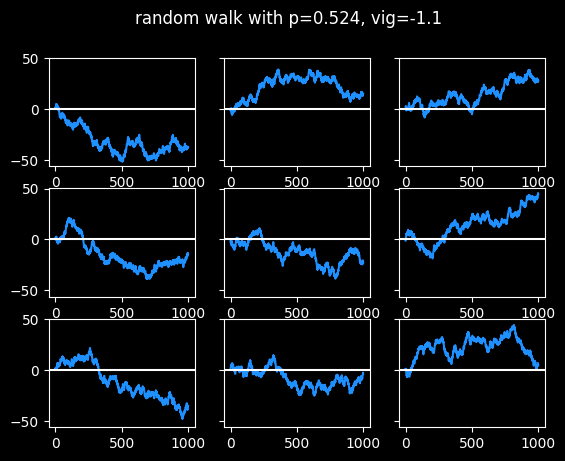

The random walks shown below are a little different from a standard one, because I'm simulating the vig. The walker goes 1 block north when the coin comes up heads (or they win the bet), and 1.1 blocks south when the coin comes up tails (or they lose the bet.)

In the marches of madness

The NCAA holds the March Madness tournament every year to determine who the best college basketball team is. It's a single elimination tournament of 64 teams, arranged into a big bracket.